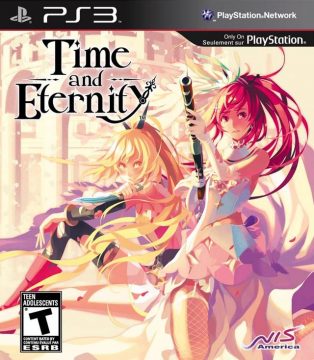

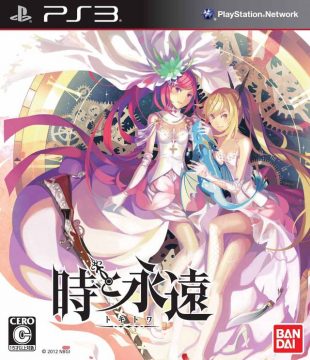

Early in development and up to its release, the most unique thing to Time and Eternity‘s name was its novel aesthetic. The way it combined hand-drawn anime visuals with a more traditional 3D world instantly caught people’s attention. It was the best of both worlds: character with high fidelity the PS3 was capable of rendering and the smooth, expressive quality that only 2D animation seems able to capture. Compared to Namco’s Tales of… series, which presented the action from a distant third person perspective similar to any number of early RPGs, much of the action is shown from an over-the-shoulder perspective, expressing a feeling of being inside of a full-fledged, living, breathing anime world. This, coupled together with a fantastic Yuzo Koshiro soundtrack, felt to be ushering in a new kind of JRPG.

Or at least that’s what people were expecting. Once the game was actually released, what people were hoping would be the game’s greatest asset turned out to be its biggest weakness. Players saw the animations as stiff and lifeless, and far from combining the best of both worlds, layering 2D animation atop a 3D world lent the experience a discomforting sense of unreality. It felt less like the characters were inhabiting the world so much as it did drawings of them were floating on top of it. Without any other distinguishing characteristics to its name, Time and Eternity was quickly forgotten, left to fade into obscurity. It also contributed to the death of Imageepoch, a company who had made their name developing mostly mediocre RPGs on portable platforms, then spent resources on this, a game which was poorly received across all territories.

The game opens to Toki and her fiance about to be wedded. Unfortunately before they can give their vows, the main character is killed, forcing Toki to travel back in time to prevent this disaster from happening. The rest of the story follows this basic pattern: Toki discovers the problem, solves it, only for a new enemy to emerge and threaten their wedding, forcing her to repeat the process once again.

Characters

Toki

The princess of the kingdom and the main character’s fiancé, Toki is a sweet, cheery, and all around innocent girl. At times, that innocence can border on childlike naivete. She’s completely devoted to her husband-to-be.

Towa

Another soul residing in Toki’s body since they were both young, you don’t even know about Towa’s existence until shortly into the game. And her personality is a stark contrast to Toki: rough, forceful, not afraid to get confrontational if the situation really demands it.

Drake

Once a knight serving under Toki, Drake soon won Toki’s love and became her fiance. Unfortunately, his entire bit is that he’s a lecherous pervert. Whenever he’s not firing off a dirty joke about what he’s gonna do with Toki/Towa, he’s gleefully anticipating the next opportunity he’ll have to leer at their figure.

It’s also worth noting that the main character isn’t necessarily called Drake, as the player names him from the start. However, he spends the majority of the game stuck in the body of Toki’s pet dragon named Drake, so out of convenience, the rest of the cast refers to him as Drake, too.

Enda

A longtime childhood friend of Toki, Enda’s only distinguishing character trait is that she’s the cute and childish one.

Wedi

Another friend of Toki’s and a planner for her wedding, Wedi’s an average character. She may be a worrywort and a bit clumsy, but other than that, there’s nothing noteworthy about her.

Reijo

The last of Toki’s childhood friends, Reijo comes across as a classic tsundere. She’s still loyal to Toki, but as her name would imply, there’s a slight high class air about her. Reijo also works as a herbologist.

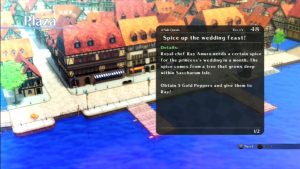

Much of the game involves helping people with daily tasks: get a quest, fight X number of monsters to collect X number of special resources (or just fight X number of monsters), and report back to the quest-giver to collect your reward. (Some quests break this pattern, but they’re the exception; not the rule). Although this framework is thematically resonant (what better way for a sheltered castle girl to grow as a person than by going out into the world and helping people with their lives?), it’s not engaging enough at the surface level for that to really function. There are 116 of these types of quests, and very little variation among them.

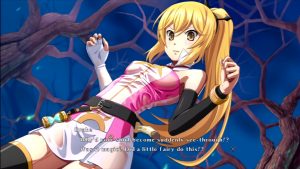

Altogether, mechanically speaking, the game’s a mess. It borrows widely from a lot of sources, including JRPGs, MMORPGs, visual novels, shooters, and a light sprinkling of fighting games, yet none of these elements work as well as they should. This is particilarly noteable in the battle system. It’s a sort of one-woman take on the party system: Toki plugs away at an enemy (either from afar with her rifle or up close with her knife) and waits for her special abilities to cue up so she can dish out stronger attacks. All the while, she’s dodging the enemy’s attacks, making sure not to get knocked back (lest she wipe out her SP bar and have to wait all over again), and timing her attacks right in between the enemy’s attack patterns. These are very busy encounters, but that’s precisely what’s supposed to make them work. Time and Eternity intelligently combines the long-term strategy of roleplaying games with the immediate action and tactics of fighting games and creates an unending flow of action. Your enemy never relents, but you don’t either as both of you vie for control of the battle. It may be tense, but that’s precisely what makes victory feel so rewarding. The visual presentation would only back that up with the powerful energy it brings to these fights.

Nevertheless, for as well as the battle system works in theory, in practice, it leaves something to be desired. It all comes down to an unwillingness to challenge the player on a number of levels. Enemies in Time and Eternity follow very simple, very robotic patterns, meaning it’s their behavior that dictates how the fight proceeds. Despite the occasional pretense the game throws up, you’re not so much dynamically responding to new situations as you are recognizing patterns and managing your time accordingly. Any overt pressures the game could have exerted on you lose whatever strength they might have had, but more importantly, giving control of the battle over to the enemies feels like a loss of agency on your part, resulting in fights that feel just as robotic as the enemies you’re fighting. Once you realize this, any excitement the encounters were meant to elicit becomes illusory, at best.

For all their promise, the fights amount to a lot of flash without any real substance to back them up. Since you only fight one enemy at at time, and other enemies simply wait in the wings until you’re done, it’s only marginally more elaborate than the original Dragon Quest. (According to an interview with the producer, the PlayStation 3 didn’t have the necessary memory to handle more than a few large sprites at the same time.) Coupled with the fact that there are only about 20 enemies, including bosses, that only vary by color, and its enemy roster is even more shallowed than most 8-bit RPGs. The scant few shooter battles (where Toki commands Drake as both take down an enemy too gargantuan for regular battles) somehow hold even less of an impact than that. The large distances and slow, drawn out pacing in these encounters ensures they feel impersonal rather than grand and epic.

Apart from the tedious structure and fighting, by far the most interesting part of Time and Eternity is the dynamic between Toki and Towa. This isn’t because their characters are particularly compelling; both are too shallow to achieve that. Rather, it’s the ideas these characters represent that make Time and Eternity just a bit richer, thematically speaking. Toki’s entire life has seen other people raising her to be the ideal princess, meaning she has to live up to every expectation that role brings with it. Most salient are the gender-related expectations, as Toki has to present herself as the spitting image of femininity: sweet, charming, innocent, ready to defer her needs and desires in favor of other people’s.

Towa, on the other hand, doesn’t have to deal with all this. Because she exists outside the regal expectations that are thrust upon Toki, she’s free to express her masculine personality all she wants. Through Towa, Toki is able to realize a degree of freedom she might not have otherwise; an ability to realize some identity outside what’s been constructed for her. The rest of the game, then, should be about how Toki mediates these two forces, how she learns to fulfill the expectations everybody has of her while still carving out her own space within them. This doesn’t mean she completely rejects her feminine side. Much of the time she spends at her house with her friends is coded very femininely, meaning she still values that part of her to a certain degree. However, embracing Towa allows her to enjoy far more than what this life could ever offer her. In fact, a lot of the gameplay systems start to connote this joyous sense of freedom when you start looking at them like this. Vast fantasy landscapes open themselves up to Toki, beckoning her to explore every inch of these spaces. And the battles have an exciting panache to them as Toki reacts to events immediately as they happen and takes action for herself.

This is what Time and Eternity could have been. Unfortunately, such a set-up would only work in a character-oriented game. Time and Eternity, on the other hand, is a player-oriented one, and it’s this set-up that leads to so many of the game’s issues. To be more specific, the game is a player-oriented dating sim. Most of your activity throughout the game is going to be spent romancing either Toki or Towa. Some of that happens through the predictable channels (discrete visual novel-esque choices), but what makes Time and Eternity unique is how it makes every other activity an opportunity to win the heart of either girl. Why do you complete quests? So you can use the Gift Points to buy Toki or Towa some new abilities. What reward does exploring the world provide? Spots where Toki/Towa and Drake can go on a little romantic excursion, some of them adding a special image to the game’s gallery. Even the items you use in battle influence each girl’s feelings for you.

Unique as this set-up may be, you have to consider it in context. When thought about along these lines, the whole dating sim focus seems to undermine the relationship between Toki and Towa and reduce them both to romantic objects for the player to do with as they please. There’s the obvious sexualization and infantilization of them – one of the gallery images is called “Suck Down That Nectar!” – but more important is the way in which this romantic focus pits Toki and Towa against each other. Unless you’re playing on New Game Plus, the game assumes you can only have either Toki or Towa, represented through their romantic feelings for you. This balance can never be equal, the game is quick to spell out in big red letters, as each girl is constantly vying for your affection.

Even putting that aside, their characters aren’t compelling enough that you’d want to learn more about them in the first place. Neither of them have any real character to speak of. Both of them make more sense as a collection of traits that make a woman (specifically, a female anime character) desirable than they do as fully fleshed out people. The game’s visuals provide a strangely apt metaphor for this predicament: characters who are so shallow, transparent, and paper thin that they fail to project any shadow onto the world.

Of course, part of the reason why they don’t feel as three-dimensional as they could be is because the writing won’t allow that. Both the writing and its execution are very low effort. Half the jokes land flat because an unenthusiastic performance, and the other half land flat because they stretch on for far longer than they ever should (some of them for minutes at a time!). Yet no matter the case, this over-reliance on cheap comedic premises does just as much damage to Toki’s and Towa’s characters as it does to the story as a whole.

And it’s not as though Time and Eternity works if you ignore all these problems. Many of them are so pervasive that ignoring them is an impossibility. But even assuming it were possible, stripping away the romantic elements leaves the game very little to work with. As much as Toki and Towa might want to explore the world, the game doesn’t provide enough reason for you to want to explore it. From a pure visual standpoint, these areas are too pristine and adherent to generic fantasy motifs to engender the majesty you’d think they’d suggest. Imageepoch’s willingness to recycle environments only exacerbates these issues. Narrative necessity aside, the only reason you’d choose to explore these areas is for the side quests, both because ignoring them creates a shortage of Gift Points (depriving Toki/Towa of stronger abilities and making it harder to woo either one) completing them should be enjoyable in their own right.

In the end, Time and Eternity‘s problems boil down to the fact that it’s unable to find its own voice. Most of the game’s foundation rests on trends that otaku have enjoyed for years, but on their own, these trends aren’t enough for a game to rely on. Even combining them won’t do it. You need to be able to justify that combination by bringing them together in a way that creates a meaningful message, or at least something that’s aesthetically pleasing. And in some ways, the game does look very impressive, but that very quickly melts away once the simplicity and repetitiveness set in. Altgoether, people were quick to forget Time and Eternity in favor of other games that did find their own voice. The game may prove interesting a few years after its heyday, but that has more to do with its failures than its successes.