Designed by comic artist Benoît Sokal and developed by Microïds, the Syberia series has become an odd little chapter in the history of point and click adventure games. It’s become one of the most treasured and remembered works in Microïds library, though not without a lot of debate attached. The series has been applauded for its art direction and surprisingly mature themes (by that, I mean actually mature as it explores themes of age and personal fulfillment and not shoot shoot bang titty curse word), but also flogged for simplistic mechanics. Still, that good will was so strong that these games have been ported all over the place, and it even earned a third game many years later.

So what makes the series stick out to so many? What does it do that’s so rare?

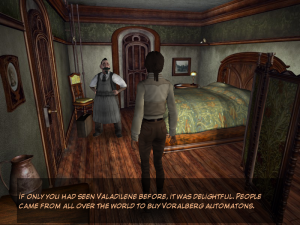

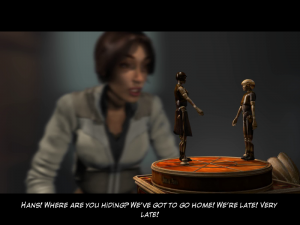

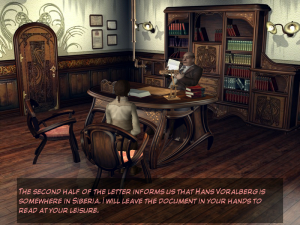

With a team of 35 people and a budget of two million euros (!), Syberia came out in the same year as Post Mortem, stemming to break away from the first person style Sokal used in his last game (Amerzone) to a more traditional third person view. The game followed Kate Walker, an American lawyer representing a law firm assisting in a deal to buy out an old factory in a small French town called Valadilène. The owner died, and a surprise heir was revealed in the form of her brother Hans, still alive somewhere out in Siberia. Thus, Kate has to track down the illusive heir and seal the deal. She also discovers that Hans was a genius inventor responsible for the factory’s signature goods, clock and gear automatons. As the game goes on, every area Kate enters becomes stranger and more dreamlike, as she’s forced to confront her feelings on the world she has to return to.

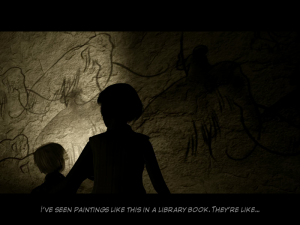

Syberia‘s setting is easily one of its strongest aspects. It does a great job of creating this exaggerated, fascinating world, as though every character in every land feels like they came out of a different story from an old pulp book. Your train’s automaton operator, Oscar, sticks out significantly for his normal mechanical detachment contrasted with his more human moments. He’s basically a steampunk C3PO. With their odd personalities and hammy voice acting, they wouldn’t be out of place in a Tin Tin serial. Every location is either in Eastern or Western Europe, and they’re all relics of the age of the great and cold wars. There’s a desolate beauty to every place you visit, with my personal highlight being an old Soviet spa still in use and clearly crumbling away into the sea. Every land also has the clear mark of Hans, as he leaves glorious clockwork machinery in every place he visits. They’re all used in truly magnificent set-pieces, including a climax involving a whole steam and gearpunk opera.

It’s also all thematically appropriate. While the story is centered around finding Hans, the narrative is more interested in Kate’s character arc, shown by the growing contrast between how she reacts to these strange new worlds and her old one that keeps calling her on her cell. Kate’s old life in America is portrayed in conversations with her boss and loved ones as a life of imprisonment through privilege. Kate’s well off, as is everyone she knows, but her life is tied around fitting into roles others want her to be. She has no real connection with anyone besides possibly her mother, but even she’s overtly materialistic at times. As the stress of Kate’s mission grows and she gets nothing but self-obsessed whining from her best friend and boyfriend, she starts seeing more and more that the search for Hans might lead her to a personal revelation. It’s a well paced out arc that contrasts perfectly with the strange adventures in rusting ruins, and it ends on just the right note.

Still, the writing isn’t quite as effective as it should be, and that’s because Kate is just a really boring character. Her dialogue lacks personality, and she never seems to react to the fascinating things she sees. It’s easy to sympathize with her, since her frustrations are practically universal to anyone in modern society, but she’s also incredibly bland, making it hard to care about her emotional growth beyond the player’s own projections.

Perhaps some of these issues can be attributed to the same problems that effect most European games not originally written in English – namely, the questionable writing and inconsistent voice acting. The translation isn’t awful, but the prose hardly sparkles, and the characters that are supposed to be weird and funny, like the dim-witted boy Momo or the eccentric rectors at the university, come off as annoying. Infinitely more appealing is Oscar, the automaton who acts as the train conductor. He’s stuffy and overtly proper, and his quirky obsession with procedure leads to a few slightly humorous moments, but his likeability stems from the similarities he shares with a certain fussy robot from the Star Wars saga. As the only real main characters, Kate’s and Oscar’s voice actors do a reasonable job with the lines they’re given, but practically everyone else’s range from despondent to atrocious.

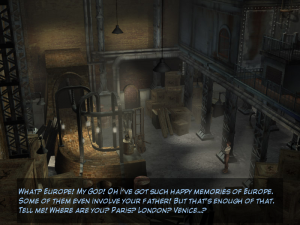

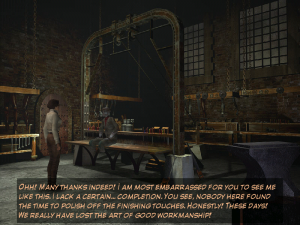

The game is also simply gorgeous, even to this day. This era in Microïds’ history is loaded with stunning looking point and clicks, but Syberia may stick out the strongest out of all of them. The art direction is some of the most jaw dropping in the company’s history, contrasting places based on real world locations with otherworldly contraptions. The moment you enter the factory in Valadilène, you know you’re in for a treat. There are so many cool mechanic wonders to find as well, including a spring loaded spaceship and a giant soviet worker that doubles as a clockwork train wind-up station. There are just so many cool ideas at work, it’s hard not to be impressed on some level.

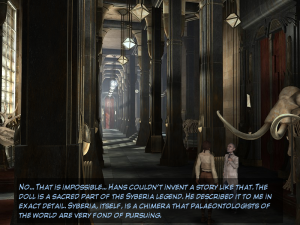

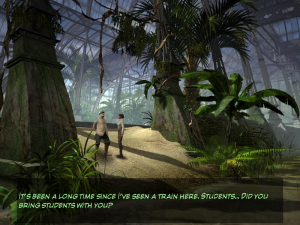

The world of Syberia is filled with some absolutely gorgeous architecture, especially once you leave Valadilene. The town of Barrockstadt is home to a majestic university, with mammoth statues that herald its entrance, and the train station is encased in a gigantic greenhouse, decorated as a man-made jungle. (This area also has several references to Amerzone, as Syberia takes place in the same universe.) The Russian city of Komkolzgrad is a contrast in that it’s terribly depressing, filled with abandoned factories that used Vorarlberg’s designs for war, yet it’s still home to some fascinating architecture, particularly the giant statues at each of end of the complex. Add in the beautiful soundtrack’s perfect blend of mood and adventure, and Syberia manages to be one of the most captivating point and clicks ever made.

Well, it would be, if not for the gameplay.

Where the game smacks right into a brick wall is how it chooses to deal with puzzles and exploration. Most every puzzle in the game is an incredible simple fetch the item affair, or has you toying around with machinery until you make a thing happen, and it’s not always clear what the thing you want to happen is even supposed to be. There’s very little satisfaction to be had from puzzles in this game, made worse by the constant back tracking. The world of Syberia is huge and desolate, which works fine for atmosphere, but not so much for practical design. You’ll be constantly running back and forth on streets and paths you’ve visited many times over, especially at the university.

The game’s second location just grinds everything to a screeching halt. First off, there’s a ton of stairs to use, and the game makes you watch Kate very slowly go up and down them every single time. I wouldn’t be surprised if all the stair climbing added at least thirty minutes to the game. There’s also a ton of ground you have to cover for every puzzle and fetch quest, which takes many minutes every time you need to make progress. The boat puzzle might be the worst offender due to you constantly having to backtrack to give instructions. If they just gave the boat owners a bloody phone, so much annoying back and forth could have been cut out.

Thankfully, everything is up hill after this area, but these issues go on for a large chunk of the game. The first area also has a similar issue, as there’s very little to do in such a large space. The initial mystery keeps it from feeling as dull as the university, though that area also has one of the few narrative drawbacks in the form of Momo. He’s kid with a mental disorder and a lot of strength who talks like a cartoon simpleton and is also a bit of a wiz with contraptions. Offensive autism stereotypes out the wazoo with this kid, and it doesn’t help that Hans is portrayed in a similar manner through letters and what little you see of him in the game. On top of that, his condition was inflicted in his back story, and Kate treats both him and Momo with a kind but condescending attitude. Syberia II completely cuts out these weird story elements, and thank heavens for that.

Syberia is a difficult game to recommend for its sluggish early pacing and rather dull puzzles, but what it does right, it does spectacularly. It has character and life to it unlike most anything else out there, and is worth checking out for the historical significance alone. But if you have some difficulty with the first two areas being such a snore, that’s perfectly understandable. Thankfully, the second stab at the series would fix that issue.

Beyond its initial PC release, Syberia also found its way onto the PlayStation 2 and Xbox, although only the latter version was released in North America. Since the original version runs in 800×600, by default the resolution had be to downsized, but the Xbox version is one of the few games on the system that supports high definition output, negating any graphical discrepancies. Obviously the control pad is cumbersome compared to the mouse, but it works just the same. In 2009 it was also ported to the Nintendo DS, in a rather ill-fitting decision. In downgrading to a portable screen, the game loses not only resolution but scale as well, removing practically all of the best elements in favor of a blurry mess. Bits of the narrative, like the newspaper clippings and even the cell phone conversations, are gone, destroying most of the depth the narrative had. Some puzzles have been removed or simplified, and the stodgy stylus-driven interface complicates matters further, to the point where it’s almost unplayable.