Owlboy was a game that took nine years to make. It started development in 2007 and finally got released in 2016. As a result of the developers’ efforts, they created the game with the goal of never having to cut corners. Director Simon Andersen was inspired by the release of the Nintendo Wii, creating a five man team from around the world and gathering awards with early build showings at various conventions. After a lot of behind the scenes legal problems, engine headaches, a main designer leaving in 2009, and breaking to make an entirely different game for one Summer (Savant – Ascent), the game eventually started to form and finally got a release. They even forced themselves to save money by communicating over Skype in their own homes instead of having a proper building for the studio, sacrificing their personal lives for this vision.

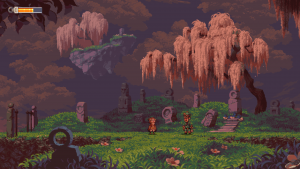

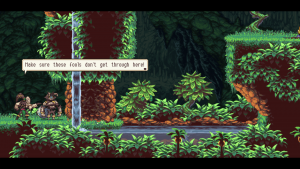

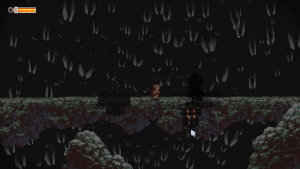

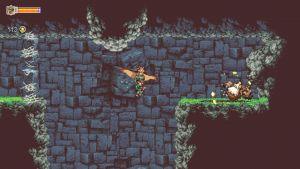

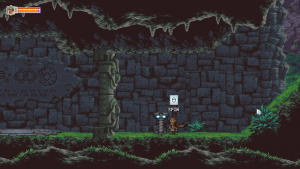

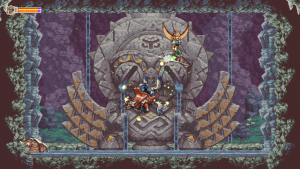

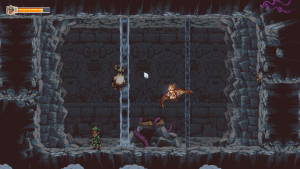

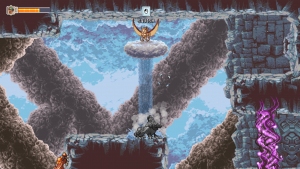

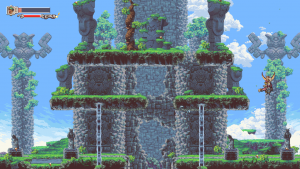

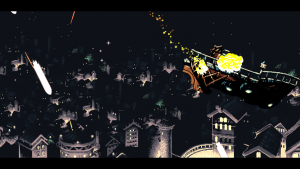

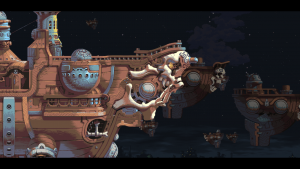

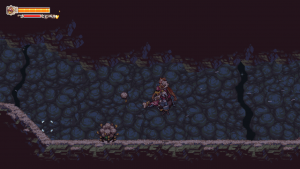

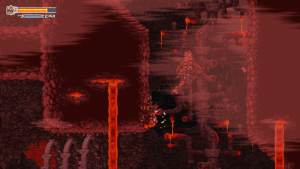

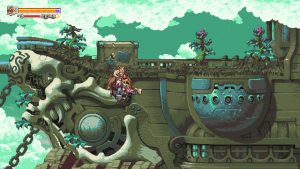

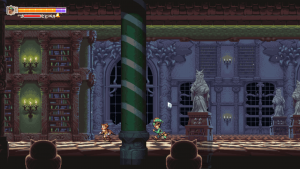

There’s a lot going on with Owlboy, but the goal the team was most vocal with was making a game that proved sprite games were still viable. Real, incredibly detailed, effects devoid sprite art. Owlboy is an artistic marvel by just the sprite work alone, only having to take a single shortcut with the inclusion of rotations for models. Everything else was completely hand done by the staff, painstakingly detailed and animated for years. It’s nearly on the level of SNK’s heyday works like Metal Slug, but even more impressive by the virtue of being made on a shockingly low budget and with only a small handful of staff members. Owlboy pretty much puts nearly every single other indie sprite art project to shame through sheer determination and effort. Every character explodes with life and color. Every action is a delight to see in motion. Every background is layered and filled with unnecessary detail only there for the sake of atmosphere. Owlboy‘s presentation alone makes it incredible art, the end result of craftsmen working their hearts out for something they truly believed in.

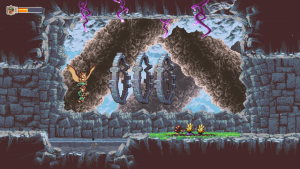

It’s a good thing the game that came with the beautiful sprite work is pretty good too. Owlboy is sort of a side-scrolling Zelda, with a few of its own twists. Its style is heavily Zelda-like, down to the character designs and technology on display. It also plays with a few familiar tropes from that franchise, mainly a seemingly normal, mute kid becoming the world’s great hero, and has a similar sense of progression. There are multiple dungeons to explore, each with their own gimmicks and styles, combining combat challenges and puzzles. Said puzzles aren’t the usual Zelda-style headscratchers based around a central item, though, as later dungeons become more focused on stealth and survival challenges, but this change gives the game its own flavor.

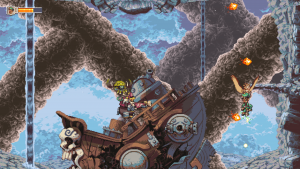

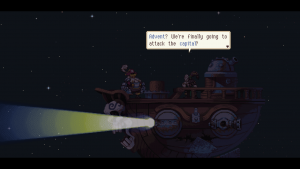

There’s a ton of focus on spectacle, which plays well with the platforming elements. Puzzles are usually traded out for big set-piece moments, like having to pilot a defeated boss through a storm of ruble or helping a wounded soldier bash through an enemy line. You can go pretty much anywhere in the world given, gaining more areas to explore as you gain new abilities. It does feel a little uncomfortable exploring, given that there’s no map function, but the levels are constructed that the way forward is usually clear, even when you need to double back to previously explored sections of the dungeons. There are also a lot of secrets to find, mainly buccaneer coins that unlock upgrades for main character Otus and friends at the only shop, and little mini-challenges to deal with you won’t see in dungeons, like one area populated by poisonous dandelions.

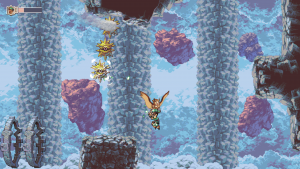

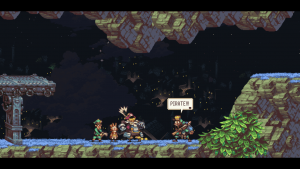

Owlboy is sort of a micro-version of its contemporaries. It gives a solid ten or more hours, but it manages to avoid padding, never outliving its welcome. The game’s central mechanics are also surprisingly innovative. Otus is a character barely able to fight by himself, only given a spin move that stops enemies momentarily. For combat, he gets three different gunner friends as the game goes on, each with their own abilities that help with both combat and traversing terrain. Otus’ role is flying his friends around.

Otus can pick up objects in the area and fly around with them freely, able to use objects for offense by tossing them in a pinch. The better solution is to keep a gunner around, whom are controlled with the mouse cursor or right analog stick while Otus is holding them. You can control where they aim and when they fire, and you can even toss them around to solve puzzles. Otus also gets a trinket early on that lets you call gunners to your position at any time, and eventually switch through them on the fly once you have a second. This all offers a lot of fun combat you won’t find anywhere else, but it’s unfortunately a tad limited for most of the game. You don’t get your third and final gunner, the most mechanically interesting of the group, until very late in the game, and the second gunner has very limited and situational use, leaving your first as the only viable option in most of the game.

Owlboy is overall a solid but not a particularly memorable game with only these merits taken into account, but its story is where it goes from good to great. See, Owlboy‘s big trick here is that Otus isn’t a player avatar that remains silent for the sake of roleplaying. He is his own character with his own motivations, goals, wants and needs, mostly expressed through his lively expressions. He doesn’t really work like Link, Samus, or the Belmonts do either, because he never gets stronger himself, only his friends get stronger. He’s not silent for self-insertion or a power fantasy, he’s silent because he can’t speak.

In other words, Otus is disabled. He’s mute.

Owlboy doesn’t begin promising a grand adventure. It begins with Otus’ mentor and guardian taking him under his wing (heh) and promising to make him a great owl like himself. The owls are a slowly disappearing race of bird people that help people in need, but Otus quickly proves himself as unfit by his mentor’s instructions. He doesn’t have particularly impressive grades, and he isn’t a particularly good flier, even once he manages to stay in the air. His mentor is constantly disappointed with him, and eventually angered when Otus accidentally tosses a pot needed to gather water and put out fires. He gets so sick of his failures that he even orders Otus to go into the village and ask people their opinion of him, played out with Otus slowly losing the ability to walk properly as he’s swallowed in darkness and shadows mock him. Even once that’s over, we still see Otus being bullied, thought as weak or inferior by the people in his village, and dismissed by his mentor and other people of authority. Heck, even when the adventure begins, Otus is implied to have accidentally empowered the game’s villain in trying to stop a thief.

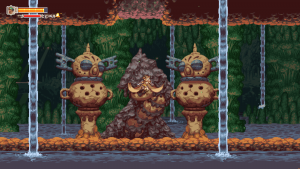

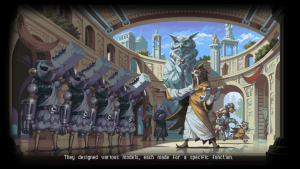

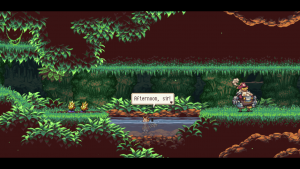

Owlboy has a lot of surprisingly mature themes mixed into its light-hearted fantasy adventure yarn. The game is very interested in commenting on fatherhood, showing three different father figures interacting with Otus. His mentor isn’t evil or trying to do harm, but he’s emotionally abusive and is the root of Otus’ low self-esteem, constantly judging him by merits that Otus doesn’t meet and ignoring what he is adapt at. The game’s main villain is another strong father figure, but taken to more horrific and openly abusive extremes as someone who leads those he should protect and guides through threats of violence, training them all to be violent and cruel people running from their true feelings out of fear, shown in full during a major late game boss battle. The one positive guardian Otus meets, Alphonse, is someone who believes in not just civility, but empathy. He judges people by what he observes and never assumes the worst upon first glance. He treats others as equals and becomes the second gunner in Otus’ group, subtly becoming what Otus’ mentor needed to be.

Otus himself struggles with his disability. It’s never tossed in your face, but it’s there in NPC dialog, as some realize he can’t speak and react to him differently. His inability to express himself is also shown to be causing a lot of strain between him and his village, only gaining respect through his actions as things become more dire. Inadequacy and insecurity pop up among many different cast members besides Otus as well, mainly with two of your gunners. Your first one, Geddy, is a soldier who lacks the talent expected of him, but manages to overcome this through sheer heart and determination. Your third gunner is also revealed to be in a very similar situation to Otus, though his family is more neglectful and disregards his feelings, even working in something that could be read as an allegory for being transgender. They’re not the only ones, as even Otus’ mentor suffers from some worries over his own inability because of how much he places on his shoulders.

As the game goes on, it tries to deliver a bunch of messages and succeeds through sincerity and careful theme construction in the narrative. It’s not a game that says you can become better, it’s a game that suggests that you don’t need to become better. You don’t have to define yourself by what your peers want you to be or what society deems you as. You are you, and you have your own talents, your own abilities, and you can accomplish great things in your own way. No matter the abuse and pain you suffer, no matter how much you tell yourself that you are not good enough, no matter how scared you may be, no matter how bad it seems, you can do great things.

It’s a game about not only learning to live with what you’ve experienced, but one that tries to teach empathy. There are monsters in the world who want nothing more than to hurt you, and you should resist them. But they are also those who don’t realize the pain they cause, or those going through their own pain and acting out of fear and frustration. There’s only one single truly evil character in Owlboy, and everyone else is either old and tired or scared and unable to communicate. We will face tragedy for as long as we live, but we will also face hope and joy. We will know hatred and we will know love. Owlboy constantly communicates that.

There are two truly beautiful moments in this game. One is the ending, and the other is a quiet moment between Otus and his mentor late in the game. As things look their bleakest, Otus’ mentor hugs him and says he’s sorry for everything, realizing he may never get another chance to say this. When the game prompts you to respond, Otus just pauses, and hugs back with all his might.

There are few games so human, so real, as Owlboy. It’s a lot of things, but most importantly, it’s incredibly human. This game took a decade to make, resulted in broken bonds and endless stress for those making it. But they finished it, and the video gaming world is better for it.