The unprecedented success of Myst inspired dozens of first-person adventure games with brain-teasing puzzles. Most of these were forgettable attempts to cash in on Myst‘s popularity, but occasionally a title rose above the rabble. Obsidian is one of these games.

The world of Obsidian is seen through the eyes of Lilah Kerlin. Along with her partner, Max, she has created the Ceres satellite, which is designed to orbit the Earth and correct environmental problems through the use of nanobots. The satellite is deemed self-sufficient, and Lilah and Max celebrate by going camping. It is on this excursion that Lilah realizes something is wrong. Max goes missing, and Lilah sees a massive, newly-created structure of black stone. She is pulled inside, where she must explore a bizarre and beautiful world constructed by Ceres. Lilah must work her way through a series of realms, each filled with fiendish puzzles that will test every brain cell she possesses.

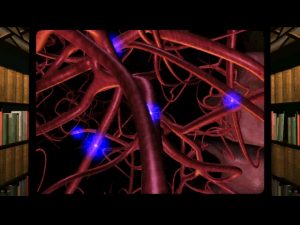

As soon as the player enters this surreal world, the astounding quality of the visual design and its implementation is obvious, with the look of the game still stunning over fifteen years after its release. With the environment presented in a series of still images linked by animated transitions, Obsidian is one of the finest examples of this type of first person adventure. The use of full-motion video is refreshingly unobtrusive and the acting ranges from decent to great. The game’s appearance is complemented by a first-rate soundtrack from Thomas Dolby.

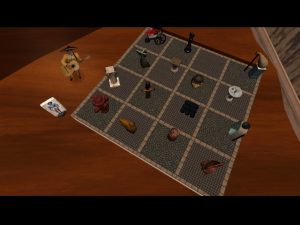

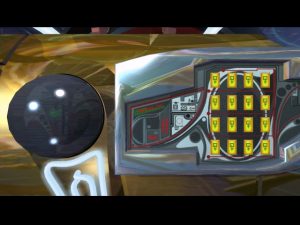

But the heart of Obsidian is the puzzles. They are what fans of this specific subgenre will care the most about, and players will not be disappointed. Puzzles are on a similar difficulty scale as those of the Myst series, and you can tell that consideration went into offering a variety of puzzles and love went into their design. There are logic puzzles, visual puzzles, mechanical puzzles, and more, though most are quite original. The difficulty varies wildly as well, as some might take a player a few minutes while others might leave someone baffled for days. In one memorable (and challenging) section early in the game, you are given a small supply of colored keycards that are used to navigate a series of nine interconnected rooms with several entry points. Different doors require different combinations of cards and also reward different cards. Despite the very clear goal and several hints, this clever use of resource management can prove puzzling. The use of inventory is limited, with the player occasionally carrying one item at a time. These items serve more to progress the plot than as the solutions to brain-teasers. There is also very little information to be kept track of, although in very rare instances it is important to remember a phrase or set of numbers for a short period of time.

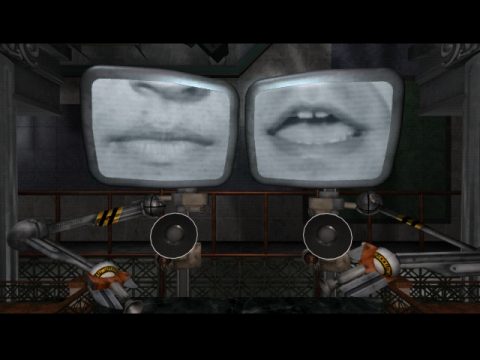

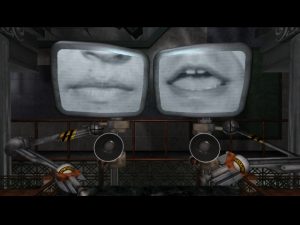

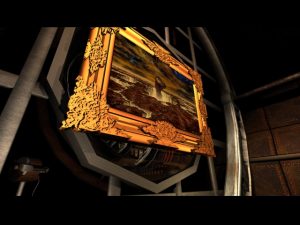

Ceres’ realms function as a hub to the game’s puzzles, and each realm has its own distinct look and feel. For example, the first area is an enormous, beautiful room containing a bureaucratic nightmare. As you explore the room, your relative gravity shifts so that you find yourself walking on the walls and ceiling. It would leave M. C. Escher feeling disoriented. The realms are based on the dreams of Lilah and Max and there is dream logic at work in how they function. For instance, you can walk through a doorway into a beautiful open field, and turn around to see the doorway hanging in the air. There is also one point where you shrink down and walk into a sandcastle as if it’s a perfectly normal thing to do. Fortunately, this Alice in Wonderland way of thinking does not carry over into the puzzles, which are as fair as they are difficult. There are a few interesting areas that exist only to be enjoyed, such as an art gallery with framed production artwork. To give an idea of the designers’ attention to detail, two files from a massive filing system are needed to advance, but hundreds of other files contain amusing illustrations just for flavor. As you explore, you’ll discover vidbots: stick-figured robots with television sets in place of a head. When you communicate with them, the screen shows a close-up of a human mouth. Many serve no purpose other than to spout witty dialogue, and one even contains a Breakout-style game.

This is not to say that the game is perfect. The limitations of the slideshow environment are occasionally frustrating. Several rooms are round, and require two screens for every step you take, making it feel like you are moving in slow motion. Like other similar games, more freedom in movement would have been nice, as some puzzles and areas are made more difficult by the limited perspective. For the most part, however, the game remains immersive and elegant.

While not commercially successful, Obsidian is an exceptional game, worth the time of anyone who enjoys an engaging story that showcases challenging, interesting puzzles. Rocket Science Games produced a landmark game with Obsidian, and they obviously had talent and creativity to spare.