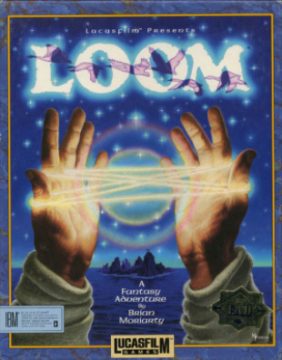

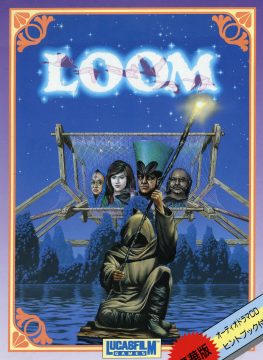

Out of all LucasArts’ adventure games, only one is rooted in the genre of high fantasy (not counting their very first adventure based off of the film Labyrinth). One might think that they would have produced more fantasy-themed games, considering that King’s Quest, the grandfather of the genre, was based on just about every fantasy fable known to man. Lucasarts often chose unconventional backdrops for their adventures, like a sci-fi/horror mansion with Maniac Mansion and Day of the Tentacle, 17th century piracy on the seas in the Monkey Island series, and a post-apocalyptic Mad Max-like wasteland with Full Throttle. There are many adventure titles based in fantasy realms, like the aforementioned King’s Quest, Quest for Glory, the Kyrandia series, and Simon the Sorcerer among others. Yet LucasArts has only contributed one original game set in a colorful world where the very fabric of reality itself is… well, literally a fabric. This game is Loom, originally released for the PC in 1990 as Lucasarts’s fourth game to run on the SCUMM engine.

Loom is the invention of Brian Moriarty, a former employee of Infocom, the company often attributed to the rise of the text-adventure genre with its Zork series. Moriarty was responsible for some of Infocom’s better titles, including Wishbringer, Trinity, and Beyond Zork: The Coconut of Quendor. When he moved up to the increasingly popular graphic adventure market, Loom was the result. The game was a bold venture for the time, as it dared to defy the very notion of death in the graphic adventure genre. It was quite common and often frustrating for such games to kill off the player for making obviously bad and unclearly bad choices, but Lucasarts decided to make things convenient for their customers. Loom was the first game in LucasArts’ graphic adventure library to institute the company’s unofficial policy of no deaths or unwinnable situations where the player will be forced to reload a save or, in the worst-case situations, restart the entire game. This made Loom notable for its time, not to mention the gorgeous graphics, fantastic sound quality, and the original plotline which made for a decent fantasy epic.

The story actually has a fair deal that doesn’t appear in the game, but can be found in a half-hour audio drama that was included on cassette tape with the original releases. The backstory is mostly gravy, as you can figure out most of what’s going on in the game itself, but it explains a few things that help to better understand the context. Loom is about the Guild of Weavers, who have grown powerful and moved on from simple cloth to sewing patterns into time and space itself. The Weavers have been ostracized for their reality-manipulating powers, cast out into a small island from the rest of the Guilds for their fearsome witchcraft. They have named their island “Loom”, after the great multicolored loom which is the focal point of their powers. Cut off from the rest of the world, the Weavers suffer and dwindle in numbers.

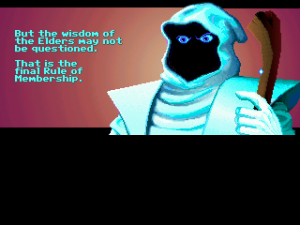

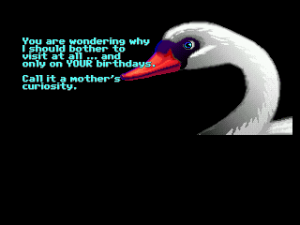

A troubled Weaver, Lady Cygna Threadbare, decides to use the great loom to help by planting a gray thread into the loom. This thread causes an infant to appear out of the loom, an unforeseen event that earns Cygna the wrath of the Guild’s Elders. Her punishment is to be transformed into a swan and be banished from the “pattern”, the universe as the Weavers had made it, essentially condemning her in between dimensions. Kindly Dame Hetchel takes in the loom infant and names him Bobbin, but she is forbidden by the Elders from teaching Bobbin any of the Weaver’s techniques. The Elders are jerks and they fear that Bobbin will eventually unravel the pattern of existence, but Hetchel believes in young Bobbin and decides to teach him about weaving nonetheless.

That’s quite a mouthful, and while not the “devil child cast away from society” story is not the most original plotline around, it’s the most developed story LucasArts has made up until this point. Despite the company’s tendencies to write their stories with a lot of humor, Loom‘s story is relatively serious (though not bereft of funny moments) and starts out on a grave note. The above backstory leads into the beginning of the game with the introduction of the protagonist, Bobbin Threadbare, the dreaded loom-child. Bobbin is summoned to the Elders on his seventeenth birthday, but when he gets to the main hall, he finds his adopted mother, Dame Hetchel, being chewed out by the Elders. They found out that she taught Bobbin about weaving despite strict orders to not do so. For her intransigence, she is subject to the same fate inflicted upon Lady Cygna; however, she is mysteriously transformed into an egg instead of a swan. Speaking of which, a swan flies in from a dimensional pocket and plays the draft of “transcendence” on the great loom, transforming all of the Elders into swans themselves! All of the swans fly off into yonder and leave the village; Bobbin is thoroughly confused after having beheld this inexplicable event.

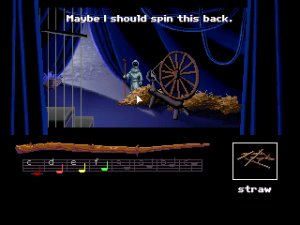

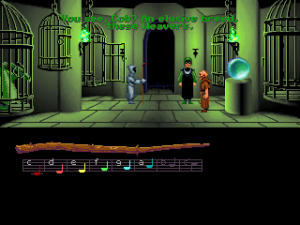

This is when the game begins proper, as one of the Elders leaves behind the ONLY item that counts as Bobbin’s sole piece of inventory. Loom was a distinct oddity in the graphic adventure genre for its time, as it shows no commands on the lower half of the screen, nor does it display an inventory. There is only one item Bobbin carries with him throughout the majority of the game: the distaff, a magical stick which has the power to manipulate the physical properties of objects. All Bobbin has to do is click upon an object (where it will be recognized by an image in the lower-right of the screen) and play a four-note tune on the distaff to cast a “draft”, a spell from his clan’s Book of Patterns. This musical mechanic is similar to the Ocarina from The Legend of Zelda: Ocarina of Time, but Loompredates Nintendo’s classic by nearly a decade.

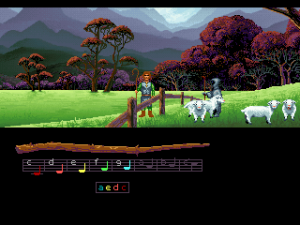

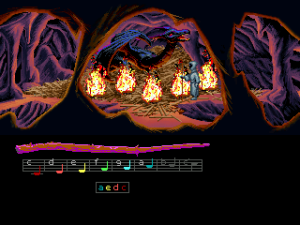

After acquiring the staff, the first order of attention is to look at the egg into which Hetchel was transformed. Doing so causes four notes to ring out from the loom, and astute observers will notice the graphic of the distaff on the lower part of the screen and the three sections of the staff with the notes of “c”, “d”, and “e” below them. The notes on the loom play out with colored sparkles, and these colors are also coded with the notes beneath the distaff. The four notes that resonate with the egg form the draft of Opening, which is always e/c/e/d, and will open up any door or container like the egg. Bobbin will learn many other drafts later, but each new game alters the notes of most drafts, except for the Opening draft and a few which are vital to the storyline. Some drafts can be played backwards to achieve their reverse affect; playing the Opening draft in reverse (d/e/c/e) makes it the draft of Closing and seals off open passages. However, some drafts are palindromes (like f/g/g/f for example) and cannot be reversed. Unlike other adventure games that involve the collection of items, Loom‘s primary gameplay consists of finding drafts and applying them to solve puzzles. Drafts are usually acquired by looking at key objects and listening to the four-note tune if they have a draft to teach. There are three difficulty levels which determine how the drafts are displayed. On the highest level, you need to recognize them strictly by sound.

It’s an innovative mechanic that lends the game a unique identity, but it does have a somewhat frustrating old-school problem. The instant a draft is learned, it is not stored in any sort of menu that can be referred to for later use. They have to be memorized or ideally written down, or else the game runs the risk of being nigh-unwinnable. (To aid this, the original release came with a book to record them.) There are a few drafts that Bobbin learns early in the game that will be used much later, and there is no way to return to the beginning and re-learn those drafts from their appropriate objects. If players don’t record these drafts, they’re all but screwed. Also, many drafts are randomized per play, so drafts cannot be recorded for one playthrough and be applied to all subsequent playthroughs. While LucasArts had decided around this time to avoid situations where the player can get stuck and have to start over, they might have still been in the experimental stages and did not recognize that players could absolutely forget drafts. Players could still attempt a painful process of trial-and-error, but it’s usually more trouble than it’s worth to attempt a guess.

Despite this problem, the adventure itself is actually quite short, and players who know what they are doing could conceivably beat the game in about an hour. Bobbin’s goal is to find out to where the Elders and the mystery swan disappeared. His adventure starts on Loom Island, which is completely barren after he frees Hetchel from her eggshell prison and she goes off to find the swans. This is where Bobbin learns several of the drafts that he will have to remember for later in the game, such as the ability to transform gold into straw, see in the dark, and… dye white objects into the color green. After learning these three specific drafts, the distaff at the bottom of the screen gains the “f” note and is able to cast drafts that require it.

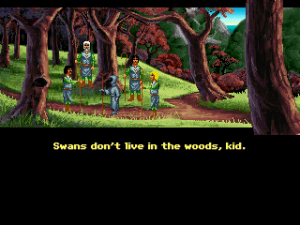

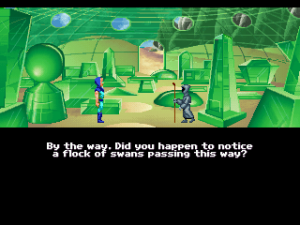

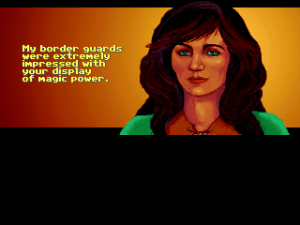

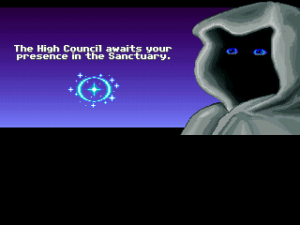

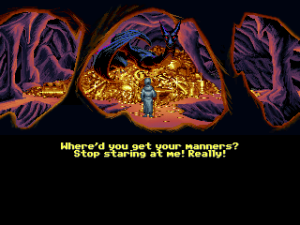

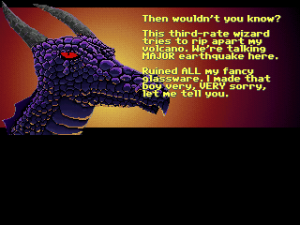

Bobbin’s journey takes him to the mainland where he comes across three other Guilds: The protective and agricultural Guild of Shepherds, the artistic and pacifistic Guild of Glassmakers, and the reclusive warmongering Guild of Blacksmiths. The Glassmakers reside in Crystalgard where the hospitable Master Goodmold shows off the radiance of their crystal city. Their most valued crafts are the Spheres of Scrying, large glass orbs that are able to see a determined amount of time ahead into the future. The Shepherds live in the Fold, a once-peaceful pasture of sheep where the livestock is constantly terrorized by a fearsome black dragon. Fleece Firmflanks, a gorgeous maiden of the Shepherds, laments that she cannot defend the sheep, but Bobbin just might have the ticket. His efforts get him abducted by the dragon itself, and he finds that this dragon does not eat humans nor breathe fire. The Blacksmiths constantly toil in the Forge, their massive anvil-shaped fortress. He finds a loafing young Blacksmith named Rusty Nailbender sleeping around an iron graveyard, and the only way Bobbin is going to get into the Forge is to commit a severe case of identity theft involving Rusty.

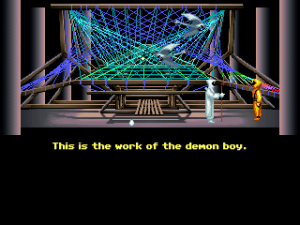

The one responsible for the disruptions in the pattern is Bishop Mandible, a callous cretin hailing from the Guild of Anti-secular Clerics who wishes to (guess what) take over the world. He somehow manages to harness Bobbin’s distaff for his own evil needs and summon the forces of the dead to rip the pattern asunder. The bastard brings Chaos, the high demon of the dead, into the world and causes… well, chaos. It all falls on Bobbin to mend the damage done by the dead and confront Chaos to try and restore order to the threads of reality. How does it all end? Rather suddenly. On the gameplay side of things, Loom becomes painfully easy after Mandible summons Chaos, and figuring out what to do takes an almost insultingly small amount of effort. The “final battle” against Chaos has the game practically shoving the correct drafts into your face, and it all culminates into a rather unsatisfying cliffhanger. It’s almost as if the game was only two-thirds finished when the developers decided to attempt an experimental method of programming the last third while sleepwalking.

Loom may be a bit light on the gameplay department, which was amusingly mocked in Sierra’s Space Quest IV, where a parody game called “Boom” described as having “no conflict, no puzzles, no chance of dying, and no interface [that] make this the easiest-to-finish game yet!” (Reportedly Brian Moriarty was none too happy about this rather good natured, if razor sharp, jab.) But it does excel in aesthetics with some of the finest visuals to be found in any adventure game of the time. The graphics gave the game’s world a whimsical appearance that reaches to just about every range of the color spectrum.

As was the case for most of LucasArts’ earlier releases, the graphics came in two distinct flavors: 16-color EGA for the original computer releases, and 256-color VGA for the others. The 16-color palette is used for the original PC release, as well as the Atari ST, Amiga, and Macintosh versions, with only subtle differences between the versions. The bright and often somewhat tacky EGA color scheme actually works in Loom’s favor and really adds to the world’s surreal fantasy appearance. The Turbografx-16 CD version uses the EGA graphics as a basis, but improves them slightly with more color and detail. The VGA graphics are still preferable, and can be found on only two of the releases: the 1991 release for the Japanese FM Towns CD home computer (which is still playable in English), and the 1992 IBM PC CD-ROM re-release.

This was the first LucasArts game to feature prominent music, as opposed to their previous titles which mostly played in silence. All of Loom‘s music is consists of excerpts from the score to Tchaikovsky’s ballet Swan Lake, which is not only fitting for most situations, but also symbolic to the overall theme, what with the swans being a vital plot point. In the EGA versions, as well as the IBM PC CD version, the music plays once before it fades into silence, but the TurboGrafx-16 and FM Towns versions have the music running throughout the entire game, adding a certain lively edge to the adventure.

Naturally, the music on CD versions is the best, and while it’s not recorded with a full orchestra like you’d find on most classical CDs, the synthesized renditions still sound excellent. The IBM PC CD version is the only one that features voice acting, technically the first dubbed LucasArts adventure, pre-dating Indiana Jones and the Fate of Atlantis by a few months. The voice acting is decent for its time, with most of the characters speaking with classy British accents, but does not add a lot of impact to the game. The problem is that all of the voices are recorded on the CD’s redbook audio tracks, rather than being compressed as samples like most other dubbed games. Since this takes up a monumental amount of space, a good deal of the original dialogue needed to be cut short and altered. Furthermore, many of the character closeups were removed, since the developers had problems lip synching the dialogue. This does not necessarily make for a worse game, because the changes are ultimately minimal, but it is a different experience that most gamers tend to deem inferior to the FM Towns version. Even though it lacks the voice acting, it has the 256-color graphics, the CD music, the full dialogue and the closeups. Thankfully, this version is easily playable on SCUMMVM, even though finding a legitimate copy is going to be extremely difficult, and overwhelmingly expensive.

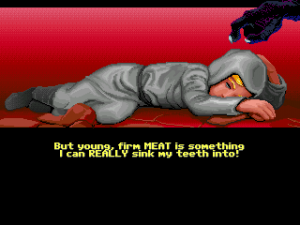

While Loom is an overall short game lacking in substance, it is still an entertaining and visually alluring adventure game certainly worth a playthrough. The dialogue is well-written, and despite being overall serious, it allows for a good deal of humorous bits, such as when the black dragon talks about her last mating season and the assistant to Bishop Mandible gets a bit too pesty with Bobbin. The graphics and sound are fantastic, doubly so on the 256-color versions of the game. It may be over too soon and ends unceremoniously, but Loom is a fine game that adventure aficionados will likely enjoy.

However, while it met with moderate critical success for its time and became a veritable cult classic in later years, LucasArts unfortunately decided to not follow up on the game’s story. Loom‘s dire cliffhanger ending is the result of plans that eventually fell through due to lack of developer and audience interest, but what could have been would have tied up the loose threads of the story (pun slightly intended). The second game, Forge, would have starred Rusty Nailbender, Bobbin’s blacksmith pal, fighting to regain control of the Blacksmith’s stronghold after Chaos and the forces of the dead wrested control of it. The trilogy’s end, The Fold, would focus on Fleece Firmflanks of the Shepherds, joining forces with Rusty and Bobbin to ultimately obliterate Chaos and restore peace to all the land, uniting all Guilds in harmony. It could have been an adventure epic in the making, but the developers of Loom were already focused on other projects at the time, and Bobbin’s quest remained the only game of its kind.

Loom is also notable for its reference in Lucasarts’ The Secret of Monkey Island. Here, a minor character from Loom named Cob appears sitting in a bar. He’s dressed as a pirate and wears a button that reads “Ask me about Loom“. When spoken to, he’ll reluctantly reply to nearly every dialogue option with a succinct “Aye”, but when asked about Loom, he goes off on a long winded spiel about how amazing the game is, while the note “ADVERTISEMENT” flashes at the top of the screen.