Kowloon’s Gate is a very difficult game. It’s not difficult in the sense that it presents challenges you’re likely to fail, but in the sense that it closely guards its meaning behind a wall of symbols and nuance. It’s a poetic game that assualts the player with symbolism around every (often very literal) corner. To achieve this, it takes inspiration from a wide variety of sources, including but by no means limited to:

- Gothic architecture

- Dante

- Carl Jung

- The New Testament

- Cyberpunk

- Wherever the idea of a mass of TVs originated from

It is not a game for the uninitiated. Yet in spite of its esoteric nature, Kowloon’s Gate has proven very popular. For a number of reasons the game has attracted a devoted following and remains fondly remembered among Japanese players even to this day.

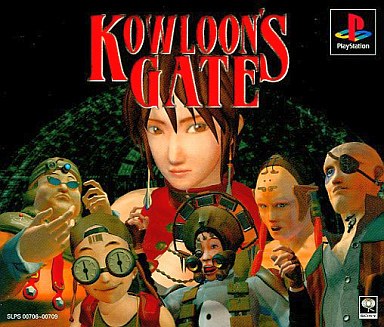

The story of Kowloon’s Gate (the game, that is; not the story the game itself tells) dates back to November 1994, about a month before the PlayStation’s Japanese release. It was around this time that work on the Kowloon’s Gate Project began, and even at this early stage, the project’s ambitious scope would have been apparent to anybody watching it. From an artistic standpoint, Zeque fused cyberpunk sensibilities with Hong Kong and Gothic architecture to create what they felt was a new aesthetic they called Asia Gothic. (This may have led to the later development of another aesthetic movement called Hong Kong Gothic.) From a production standpoint, the game was equally ostentatious. It made the rounds at all sorts of shows and expos, each time giving out all sorts of promotional material (jackets and T-shirts).

Some of this may be attributable to Sony’s involvement with the game. After all, Kowloon’s Gate was released in a time when Sony was very concerned with courting talent from independent game developers. But even in context, the fervor surrounding Kowloon’s Gate stands out. What’s more, it continued through the game’s release. An early special edition of the game came with a 108 page hint book (made to look artificially aged) that not only gave hints about how to progress through the game, but also outlined the thought process that went into its creation. Even the four discs the game came on were incorporated into the game on a thematic level: they were made to look like silk maps leading to the Four Symbols and were even numbered as such (Byakko, Genbu, Suzaku, and Seiryuu, respectively). Finally, figures of some of the game’s characters (see below) were sold for a limited time.

All that’s left to describe is the game itself. But before that happens, it would help to go over some concepts from Chinese philosophy/history that are vital to understanding the game. (Kowloon’s Gate invokes some of them frequently and expects players to understand what all of them mean.)

Tao / Dao

Usually translated as “The Way”, Tao is both a philosophical/religious system and a discrete concept within that system. To elaborate on the latter, it’s been described as “the ultimate creative principle of the universe” and “the process of reality itself, the way things come together, while still transforming.” The goal of the system built around this principle is to align one’s self with the Tao to achieve inner peace and harmony with the cosmos. Theoretically, that task is very difficult to achieve. Given the enormous scope of the Tao, it defies any conscious understanding of it, let alone an easy understanding. In fact, it’s been said that “the Tao that can be known is not the Tao.”

So in lieu of directly knowing it, Tao encourages forging a raw, personal understanding of the it that one lives intuitively. In practice, this means dispensing of conventional logic and societal/cultural assumptions, discovering one’s true inner nature through the Tao, and then living that nature as effortlessly as possible. Tao can also be viewed as an early form of dietary science. Early proponents of Tao advocated for spiritual longevity, healthy living, and the pursuit of immortality through the Tao. To that end, they’d prepared specific advice such as abstaining from grains to starve the Three Corpses living in one’s body. (The Three Corpses are the center of a minor narrative arc in Kowloon’s Gate.)

Qi

A metaphysical concept referring to a natural creative force that’s necessary for life to flourish; sometimes translated as “life breath.” It links living beings with the universe around them. Because qi is constantly flowing through the environment it’s often understood through natural forces, although it should be noted that qi expresses itself through those forces rather than being interchangeable with them. This is most easily seen in the Wu Xing, the five classical Chinese elements and a system for describing the flow and metamorphosis of qi.

Feng Shui

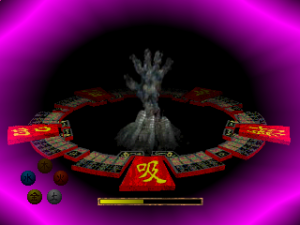

The study and practice of qi, especially as it relates to the environment. More specifically, feng shui is the practice of directing qi to promote a healthy flow of life energy in the surrounding environment. Broadly speaking, there are two schools of thought on how to achieve this. The Form School looks to immediate features in the area – rivers, mountains, forests, etc. – and decides its course of action from there. In fact, this is where the name feng shui comes from. The two characters in its name refer to wind and water, respectively; together, they refer to a saying about how qi gathers in the water and scatters on the wind. Kowloon’s Gate, on the other hand, seems to derive from the Kanyu tradition of feng shui. Instead of reading things in the immediate world, this tradition uses a qimancy board to read constellations in the sky. The theory was the constellations and their movements could predict every facet of human existence, at least in a broad sense.

Yin and Yang

The concept of yin and yang is somewhat similar to binary oppositions, although there are important differences. First, yin and yang are understood as metaphysical concepts rather than strictly linguistic ones. In fact, the eternal ebb and flow between yin and yang is considered necessary toward the functioning of the cosmos. Second, unlike binary oppositions, the opposition between yin and yang isn’t interpreted as putting them in conflict with one another. They create harmony because of their mutual opposition. The literal translation of yin and yang is “shade and sun”, respectively, but these aren’t the only concepts associated with yin and yang. A comprehensive list of things associated with yin and yang can be found here.

Granted, these topics are much more complex than what’s been described here, but a basic summary should illuminate recurring themes. To start with, these branches of Chinese philosophy assume that humans are ultimately the products of the environment they inhabit. Both may be just points in the much larger web of existence, but because the world’s existence far exceeds human existence, the best course of action is for people to build their lives around their environment in such a way as to ensure harmony with it.

The second major theme here is existence as being in eternal flux. Everything is in a constant state of change, and the only thing that allows people to see meaning in the world is the ever-changing relationship between two diametrically opposed forces. Thus it doesn’t make sense to see things in nature (or nature itself) as being stable. If anything, the opposite holds true: to ensure balance in the world is to ensure this process of change continues in a healthy manner. Why is the constant flowing of energy associated with life? Because the flow of energy amounts to the constant replenishment of said energy by making it sure never stays in one place long enough to stagnate. (Tao extends that to a spiritual level, reading the human mind as a site of chaos and destructive struggles the Tao practitioner has to sort out.) And perhaps most important of all, these processes are all facilitated through a connection with nature, the medium by which creative life energies express themselves.

But what happens when that connection is severed and the people are left unable to form any sort of connection with the natural world? How does one ensure the proper practice of these philosophical concepts in a context that’s almost entirely divorced from nature? The historical Kowloon Walled City seems tailor made to answer those questions. Remembered as the most densely populated city on Earth at the time of its demolition, Kowloon Walled City was the product of a long chain of historical accidents. The City originally started as a minor military outpost dating back to the Song Dynasty. It would spend the next several centuries languishing in obscurity until the 19th century when, following the Opium Wars and the ceding of Hong Kong to Britain, the fort became a key defense against further British incursions. Following the events of 1898, the city ended up in a sort of Limbo where it was ostensibly under China’s control but neither China nor Britain fully controlled it.

However, the history of the Walled City proper begins at the end of World War II. The Japanese military occupied the city during the War, and following their evacuation, thousands of refugees and squatters fled into the city. At its peak over 50,000 people were living in just a few blocks’ worth of buildings. Structurally speaking, the city was a mess of improvised architecture that wasn’t built to code. Pipes were leaking, wires were dangling, and sunlight was all but closed off to the city’s inhabitants. Some corridors were so dark that not even the police dared venture through them. As a result, crime flourished in the City. At best, those crimes amounted to things like unregulated medical care and meat processing without any health or sanitation oversight. At worst, it involved things like the Triad, “brothels, casinos, cocaine parlours and opium dens.” No wonder, then, that the Cantonese nickname for Kowloon Walled City was “The City of Darkness.”

For many outsiders, this was the only view they had of the Walled City. Yet the people who spent their lives inside those walls remember their time more fondly. In one sense, living in the city was an act of resistance whereby people could escape the government’s reach and claim control of their lives for themselves. More to the point, the Walled City gave the destitute a number of affordances when they didn’t have much else: low rents, no taxes, no government documents to worry about. True, the standard of living was low, especially since the lack of government officials meant limited amounts of welfare, but these conditions only strengthened ties within the community. Without anybody else to look out for them, the people of Kowloon could only rely on each other. That’s why former citizens of Kowloon Walled City remember the loyalty and friendship between each other the most. (In addition, the lack of formal architectural training and the improvised nature of building things led to unique building designs that are still closely studied today.)

Still, the conspicuously low standards of living and the flagrant (not to mention successful) violation of the law must have embarrassed both Britain and China, neither of whom wanted much to do with the city. The fact that Kowloon Walled City was just outside an international airport, as if on display for the whole world to see, would have only magnified that embarrassment. Several times, the Chinese government either tried to reintroduce the rule of law to the city or destroy it completely, but none of these attempts were all that successful. It wasn’t until 1994 that the government was able to forcefully evict the citizens and demolish Kowloon Walled City for good. Today, the site is occupied by a park erected in the City’s honor. Some artifacts from the city remain, but much of it has been replaced with aesthetically pleasing natural exhibits and traditional Chinese architecture. Kowloon’s presence and everything it once represented has been erased.

Kowloon’s Gate begins by negating that erasure. Its story takes place in the modern day (1997), four years after the destruction of the Walled City. Suddenly the City re-emerges from the world fo Yin, a world of negation that’s said not to exist in its own right. That it emerges into the world of Yang poses a serious threat to the world. If this crisis isn’t taken care of soon, then Kowloon Walled City will throw the world into chaos by halting the intermingling of yin and yang. As a representative of the Hong Kong Supreme Feng Shui Conference, it’s your duty to enter the newly emerged Kowloon, locate the Four Symbols, and restore order to the world. In practice, this means gathering information and restoring harmony to Kowloon by purging various locations of the unwelcome spirits (gururin) roaming about them.

A couple of things to note before listing characters: first, because of the sheer number of characters Kowloon’s Gate (any one of whom could be important to the plot at any given time), this article will only focus on those with the greatest or most immediate presence in the narrative. Second, although the official Kowloon’s Gate site provides its own romanizations for the characters’ names (hidden in the URL for their respective pages), those names aren’t very reliable. Many aren’t translations per se, but transliterations from Japanese. Obvious misspellings, inconsistencies and strange naming conventions abound, so this article will abandon those names in favor of ones that make more sense.

Protagonist (Note: no image provided because his appearance is never shown over the course of the game.)

A representative of the Hong Kong Supreme Feng Shui Conference, the protagonist is a feng shui practitioner sent to investigate the mysterious re-appearance of Kowloon Walled City. Other than that, his identity remains a mystery. The only name he’s ever given is his online handle, 辰387-壬 (the characters are Chinese and don’t seem to mean anything). But judging by his behavior, he’s a disciplined practitioner and an ideal Tao sage (section 5).

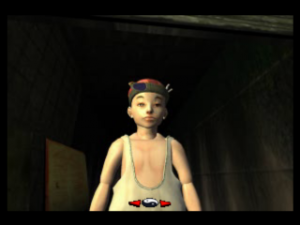

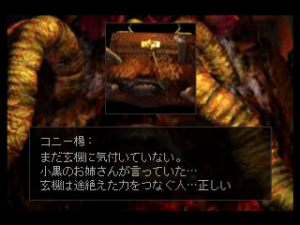

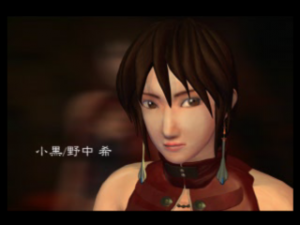

Xaohei

A resident of Kowloon. Depending on how you interpret her, Xaohei is either the story’s deuteragonist or arguably the real protagonist of the story (since her actions do so much to drive the story forward). She initially works with the protagonist so she can better understand her own spiritual experiences – her strange dreams, her older brother/sister (a distinct spiritual concept in the game), the Day of Fire – and how they relate to the city’s mysteries. Eventually, though, Xaohei decides to take things into her own hands, both to further her own understanding and to help the protagonist in his own quest. Although she ends up just as lost and helpless as everybody else who tries to understand Kowloon, her actions pose a severe threat to the powers that be. Xaohei is the only non-Navigator character to have an official figure made of her.

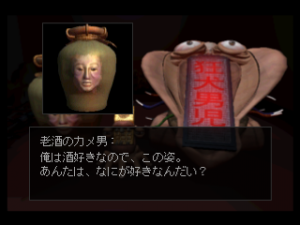

Rich

The owner and runner of the city’s tavern, Rich is a helpful character who’s willing to help the main character by giving him whatever information he finds. Because of this (and his character design in general), Rich and his tavern lend the game a sort of spaghetti Western atmosphere whenever they enter the story.

Mirror Salesman

One of the first characters who makes any real effort to understand the Walled City, and one of its first victims. After the protagonist rescues him from his Dante-esque punishment, the Mirror Salesman provides him aid in return. This mostly happens throughout the first half of the game.

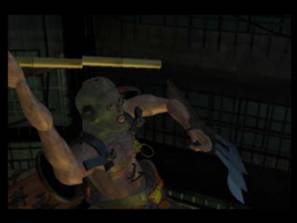

Mister Chen

A local crime-lord (leader of the Snake Syndicate) with an iron grip on many of Kowloon’s businesses, Mister Chen is the first real villain of the game. Where the protagonist seeks to heal Kowloon and its people, Mister Chen is very much interested in maintaining the crime-riddled status quo he stands to benefit from. And because he believes there’s nobody who can oppose him, he doesn’t even bother to hide his corruption or his brutal violence. As the story advances, though, it becomes very clear that there are much larger powers at play.

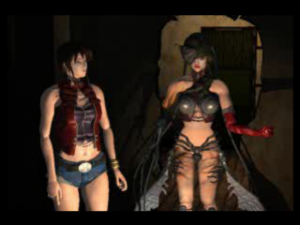

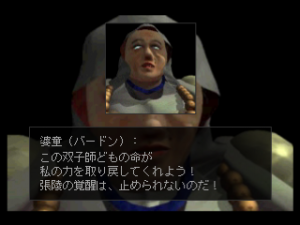

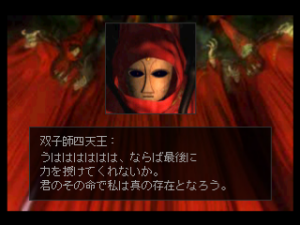

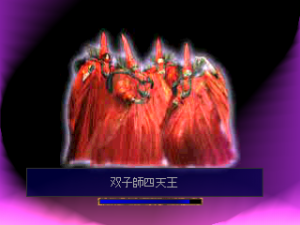

The Twins

Mister Chen’s lackeys, the Twins’ methods aren’t nearly as violent as their boss’s. They’re most often seen promising some form of spiritual enlightenment, whether that’s by connecting people to a power that’s been sleeping inside them or by awakening them to their true selves. However, it’s clear that this is more a method of keeping Kowloon’s populace under their control than it is a legitimate spiritual practice.

In addition, there are the Navigators whose job is to guide the protagonist through Kowloon’s various dungeons.

Little Fly

He flies through each dungeon on a hovering motorcycle. He’s more casual compared to some of the other Navigators, but oddly the least talkative among all four. However, this is likely because he’s the first Navigator in the game and the dungeons he’s available for aren’t as complex as the later ones, meaning less guidance is necessary.

Bamboogee

Bamboogee’s name is a source of confusion, since it could either be a reference to his age (it ends with “jii” (じい) a suffix meaning “Gramps”) or a portmanteau of “bamboo” and “bungee”, referring to the trapeze artist aspect of his character. Either option is equally likely. Other than that, there’s not much to note about him. He’s close to Honey Lady in terms of personality and navigation, with only minor differences separating the two.

If Kowloon’s Gate has one strength, it’s its impeccable eye for detail. Looking at the big picture, the City’s sprawling layout is immediately obvious to anyone who plays the game. And looking at it in finer detail, anything that could have been gleaned about the City’s existence is almost guaranteed to appear in the game one way or another. The imagery makes that perfectly clear: the local crime lords, the open water, the tight corridors, the dangling wires, the refuse littering the streets, the buildings closing out the sunlight – all of it appears at one point or another. Even minor details like the meat packing industry or the out-in-the-open medical treatment find their way into the game.

Yet the game’s eye for detail isn’t limited to imagery. It also applies to how you play the game. One trend throughout the design of Kowloon’s Gate is its tendency to take well known game mechanics and modify them slightly to fit its own agenda. For example, the game clearly fits into old adventure game conventions: the story advances once you’ve collected certain items and used them in the right places. However, those items very rarely leave your inventory. They stay there long after they’ve fulfilled their purpose, slowly gathering up like trash in the city’s streets. It’s almost like the game is saying the Walled City can only be healed according to its own logic rather than by anything outside it.

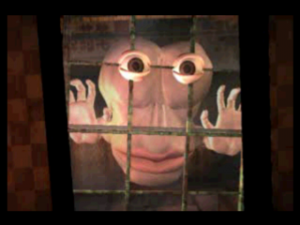

Something similar occurs when it comes to creating a sense of place. Although Kowloon’s Gate is (mostly) an FMV game, the dungeons are all rendered in real time. Because of this, they don’t stress movement like the FMVs do, but place. And as would be appropriate for any depiction of Kowloon, the buildings have an impromptu, slapped-together quality to them: tight hallways, angles that make no sense, doors that lead nowhere (or simply never open), etc. They’re best described as a sort of non-place; a location so confusing, so unstable, that it confounds any attempt to read a sense of place into it. Ironically, it’s exactly what Kowloon’s Gate would need if it wanted to create an authentic sense of place.

The dungeons also serve as a good illustration of the game depicts not only Kowloon Walled City, but the various spiritual crises its existence brings up and how those crises should be handled. Despite their various designs, the flow of each dungeon is essentially the same: you begin by slowly combing over the area, using all the measured judgment of a feng shui practitioner to tease out where the disturbance is. A pink glow indicates a gururin is nearby; a green glow indicates the gururin will only disappear when the core cause of the disturbance is addressed.

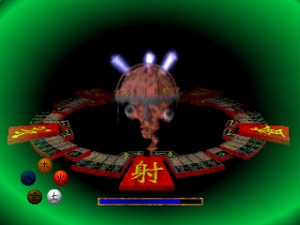

When you finally encounter a gururin, the environment melts away as the two of your are locked in combat. At first, it looks like the game runs on a basic turn-based battle system: you can either strike the enemy with a ceremonial sword or attack them with one of the five elements. On closer examination, though, the system turns out to be more complex, operating on a sort of draw/discard mechanic. The sword draws out whatever element the gururin is holding onto, meaning if you already have it, it won’t work. Possessing all five elements at any one time is also something to be avoided, since it results in an immediate (not to mention potentially gory) game over. To avoid this scenario, you attack the gururin with whichever element will conquer it according to the Wu Xing. In other words, the game incorporates feng shui directly into its design: you gather up errant qi with the sword and scatter it with the elements to bring equilibrium to an unbalanced area. All the game’s little touches only further demonstrate its understanding of those principles, such as elements generating other elements the longer you stay in a dungeon (although for some reason, changing a gururin’s weakness doesn’t follow this or any logic).

The dungeons aren’t the only place where that understanding manifests. Because Kowloon’s Gate is mostly an FMV game, it’s perfectly equipped to explore the spiritual problems the City poses even outside of dungeons. Being early experiments in moving cameras through 3D space, contemporary FMV games (like D and Lunacy) were known for their floaty, aphysical movement, something Kowloon’s Gate both realizes and develops on. You’re not so much a person moving through the world as a process following the erratic flow of qi the city’s haphazard layout creates. As a result, movement feels erratic, like you’re a ghost wandering through the city in a drug-induced stupor.

Of course, it’s unlikely any of this has anything to do with why Japanese players became so enamored with the game in the first place. After all, Kowloon’s Gate is the kind of game that assumes you understand Chinese mythology/philosophy and is unforgiving toward those who don’t. The real reasons why there’s so much nostalgia for the game are more banal. First, not only did the game come out during the heyday of FMV games, it even tried to create a Japanese equivalent of the name with “JPEG dungeon”. (Judging by Google search results and the Japanese version of Steam, that attempt was unsuccessful.)

And compared to its contemporaries, Kowloon’s Gate is a much more narratively mature video game. What initially looks like an esoteric game about these abstract metaphysical concepts escalates into a spiritual journey; one that involves genetic engineering and legends of immortality; full of intrigue and spanning all of space and time. This doesn’t mean the story’s philosophical dimensions go away. Kowloon’s Gate is more literary in nature than its peers, which generally look to action movies or similar areas of pop cinema.

In one sense, this means the game isn’t afraid to embrace complexity wherever necessary. Abstract symbolism abounds, and the story is full of concepts the writers invent for their own purposes (wannin, the older sibling point, minri, the Day of Fire, etc.). But in another equally important sense, Kowloon’s Gate doesn’t pursue complexity for its own sake. It deploys these concepts carefully, and at all times the story maintains a firm grip on things like pacing, mood, etc. To pick an example from late in the game, characters like Xan Ji (a sentient pile of goo) and the onmyouji lighten the mood whenever circumstances threaten to become too gloomy. It should go without saying that this level of control also applies to the cinematic techniques, with their distinctive shots and the purposeful way the camera frames and moves those shots.

Putting aside how the game is presented, Kowloon’s Gate is primarily remembered as this cyberpunk beauty of a game, a reputation that isn’t unearned. All the classic hallmarks of the genre are there: the grimy future aesthetic, the complex web of conspiracies, the distrust of a modern world that only breeds feelings of anxiety, alienation, and emptiness in its helpless populace. In that regard, the game shares a lot with popular cyberpunk works like Akira and Shadowrun.

At the same time, the game doesn’t just utilize whatever techniques people expect from the genre, but expands on them and modifies them to fit its own vision. The Asia Gothic aesthetic makes that perfectly clear, and the narrative serves to further illustrate that unique identity. While there are several clandestine powers controlling the fate of Kowloon, it’s difficult to say the conspiratorial atmosphere stems from those powers. If anything, that atmosphere is just part of the city and another reflection of its spiritual crisis: people understand so little about their situation not because that knowledge is being closely guarded, but because it (or the powers connected to it) are so far beyond human understanding that those who obtain it go mad from the revelation. Likewise, the game uses its time travel opportunities to show how the people’s existential malaise isn’t the product of an oppressive modern world; it’s something written into the Walled City itself.

Unfortunately, this hints at a significant problem with Kowloon’s Gate and a weird irony at the heart of its design: for all its talk about reviving a lost spiritual connection with the world, the game itself isn’t as connected to reality as it wants you to believe it is. In fact, it seems almost eager to leave the City’s strict confines so it can flex its creative muscles. This works to the game’s benefit when the story ventures outside Kowloon’s walls, but such opportunities are rare. Thus the game can get ahead of itself, forcing the City to bend and contort to fit the larger messages at play, even if the end result doesn’t make any sense. As studied as the City’s architecture was, it’s highly unlikely spacious Roman-style aqueducts were ever a part of it, especially ones adjacent to a 19th century-esque asylum.

More broadly speaking, Kowloon’s Gate was made by a team who had always stood outside the City, meaning the game emphasizes the exotic: the crime syndicates dominating affairs and the bleak suffering the city inflicts on its inhabitants. This isn’t to say the game is unsympathetic to their plight – its desire to heal them is genuine and it still holds out hope that their lives will improve someday – but that the context in which Kowloon’s Gate was made constrains the sympathy it does have.

There may be a spiritual dimension to the Walled City, but that doesn’t make the City itself a source of spirituality, or at least not a spirituality the game thinks is worth admiring. As far as the game is concerned, the City can only confuse and disorient a people who are helpless before it. However, this overlooks the ways in which the people of Kowloon managed to practice their spirituality. Moreover, the spirituality the game offers to fill the gap may not always have a place for the people of this Kowloon. It doesn’t help matters that the game’s interest in powerful figures (Mister Chen), colorful personalities (the Twins), or large scale salvation crowd out any appreciation of the average citizen.

All of this reaches a head when you consider the City itself, since Kowloon’s Gate re-enacts the ultimate history of Kowloon without ever really questioning. If anything, the game goes out of its way to justify that history. Non-existence, it argues, is Kowloon’s natural state of being. Its violation of that nature by asserting its existence once again amounts to a spiritual disruption, one that poses a grave threat not only to the area but to all human existence. Its fate was quite literally decided from the game’s opening moments: a violent destruction actively willed into being rather than a passive fading out of existence on its own terms.

A yin/yang interpretation of the plot and its two principal characters only further brings this into relief. On one end there’s the protagonist: a (presumably) male feng shui practitioner who enters Kowloon from the outside city of Hong Kong. In the end, he leaves the plot intact (and on a sunny day, no less). Contrast this against Xaohei, the female native of Kowloon. She lives only in shadow, a fact reflected in her driving the story forward from behind the curtains, and she must ultimately die to fulfill her destiny. It says a lot about Kowloon’s Gate and what the developers were hoping to achieve with it that the official site devotes so much space to explaining its own vision, but the one section allotted to the real Kowloon is still under construction two decades later. There are other faults with Kowloon’s Gate, like the somewhat repetitive special battles or the story’s complexity resulting in overly confusing symbolism, but these are minor problems in light of what’s just been described.)

Both Japanese and English sources are unclear about what Zeque did following Kowloon’s Gate. They teamed up with Quintet to make the PS1 action-adventure game Planet Laika a few years later, and some of the imagery in that game harkens back to scenes from Kowloon’s Gate. Other than that, what became of Zeque is unclear. Because they teamed up with other developers to create their games, some sources (like GameFAQs and the Japanese Wikipedia page) will list them as the game’s developer instead of Zeque. Still, Kowloon’s Gate was both a financial and critical success. It was re-released as an Artdink Best Choice title in late 2000, and Sony at least explored the possibility of translating it. There are rumors that a small number of translated copies exist, but given the lack of translated material in the trailer, it’s very unlikely any real progress was made on the translation.

The game also attracted a following that remained active long after its release. A 2009 Famitsu poll of most wanted sequels saw the game place tenth. In 2016, a group of fans took the project into their own hands: a VR remake of the game is currently in the works, and when the creators launched a crowdfunding campaign for it, the project met its goal within 24 hours. Maybe this will be the second chance the game needs to reach a wider audience outside Japan.

Links:

Kowloon’s Gate walkthrough

Official site

Kowloon’s Gate VR

Sources on Kowloon Walled City and Chinese philosophy/religion:

http://www.fengshuigate.com/qimancy.html

http://www.cnn.com/2014/03/31/travel/kowloon-walled-city/

http://www.bbc.co.uk/religion/religions/taoism

http://www.iep.utm.edu/daoism

http://www.goldenelixir.com/taoism/yin_and_yang.html

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=dj_8ucS3lMY

http://www.dailymail.co.uk/news/article-2139914/A-rare-insight-Kowloon-Walled-City.html

http://www.scmp.com/news/hong-kong/article/1191748/kowloon-walled-city-life-city-darkness

http://www.cnn.com/2014/03/31/travel/kowloon-walled-city/

http://www.patheos.com/Library/Taoism/Beliefs/Suffering-and-the-Problem-of-Evil