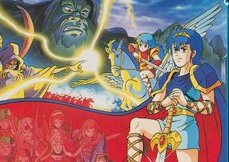

- Fire Emblem (Introduction)

- Fire Emblem: Ankoku Ryu to Hikari no Tsurugi

- Fire Emblem Gaiden

- Fire Emblem: Monshou no Nazo

- Fire Emblem: Seisen no Keifu

- Fire Emblem: Thracia 776

- Fire Emblem: Fuuin no Tsurugi

- Fire Emblem (GBA)

- Fire Emblem: The Sacred Stones

- Fire Emblem: Path of Radiance

- Fire Emblem: Radiant Dawn

- Fire Emblem: Shadow Dragon

- Fire Emblem: Shin Monshou no Nazo

- Fire Emblem Awakening

- Fire Emblem: Fates

- Fire Emblem Echoes: Shadows of Valentia

- Fire Emblem (Misc)

Fire Emblem is the “original” console strategy RPG, a genre that was previously bound only to computers. Designed by Intelligent Systems, a division of Nintendo, Fire Emblem was the brainchild of Shouzo Kaga. This mix of RPG-style character development, growth and storyline focus coupled with the tactical placement of units on maps of War Simulations (dubbed SRPGs or simulation role-playing games) became one of Nintendo’s most popular franchises in Japan, and has directly influenced every major SRPGs since then in one way or another, including Shining Force, Langrisser, and Tactics Ogre.

Throughout its many installments, Fire Emblem has retained many core characteristics that have been carried over from game to game. Most characters can wield at least two weapons (usually a spear, an axe, or a sword), which have various strengths and weaknesses. These weapons wear out from use, requiring to constantly obtain new ones. In most games, the shops are located on the battlefield, so you might need to take one of your characters out temporarily to have them stop by at a local store to restock. Characters can also visit houses on the battlefield to chat with the locals. Units also tend to talk to each other during a battle to reveal extra story tidbits or strengthen their power. In some cases, you can even recruit enemy soldiers on your team. Most games feature a huge roster, often centering on a handful of primary characters, accompanied by dozens of secondary characters.

The funny thing about a lot of strategy games is that so few honestly feel like they were focused on strategy. Real time strategy games are often more about micro managing growing throngs of units or dealing with more and more types of resources. Other strategy RPGs focus too much on the customization elements, where gaining levels and optimizing combinations of skills are far more important than tactical placement on the map. Fire Emblem, on the other hand, demands that you create and execute a sound strategy, as opposed to masking its difficulty in exponentially increasing layers of numerical bureaucracy. It strikes an optimal balance between offering enough complexity to feel deep and keeping things simple enough to not become cumbersome. Sure, leveling up is still very important, but you can’t just grind your characters to victory. Instead, you’re encouraged to balance them out and pick your battles wisely. In most of the games, battles cannot repeated, so there’s only a limited number of experience points to be had. If you focus only on a few characters, the rest of the roster will become incredibly weak by the end of the game. Many of the titles have one extremely overpowered character (sometimes called “trap” character), which can cause lots of damage but doesn’t gain much experience. They’re helpful, but you need to spread out your attacks so your experience is better distributed among the team.

The enemy AI is surprisingly smart, striking viciously at weakened opponents and doing everything it can to ensure its victory. Perhaps Fire Emblem‘s most controversial elements lies with permanent player character death. Yes, once a character is killed, that’s it – they’re gone for the entire game, and (usually) there’s no way to resurrect them. This requires that you carefully consider every move, especially when maneuvering weak units like magicians or healers. While this aspect often frustrates obsessive-compulsive players who refuse to give up any of their characters, the later games in the series tend to toss enough units into the roster that you can spare to lose a few and not have to worry about becoming outnumbered. If you play semi-compentently, you’ll probably have more characters than you know what to do with, anyway, because many missions limit the number of units you can take into battle..

There are tons and tons of different character classes – swordsmen, axe wielders, cavalrymen, heavy knights, archers, magicians and healers. Most units can only attack if they’re adjacent to one another. Spearmen, magicians and certain axe wielders can attack diagonally, or two spaces forward. Archers can attack two spaces away, but can’t attack anything directly adjacent. Heavy knights are slow but extremely powerful. Calverymen (in the later games) can move again after attacking. Pegasus knights have huge range but often suffer from poor defense.

It also utilizes a class promotion system. Once characters reach a certain level (and in some games, when they use a certain item), they transform into a more powerful unit, and their level is brought back down to one, creating more room to power them up even more. The Fire Emblem games are a bit weird in that the stats are upgraded randomly when gaining level, as opposed to the fixed stat growth in most other Japanese RPGs. This means that some characters may end up being more powerful than others, even when using them evenly.

Despite its many iterations, there has been very little change in Fire Emblem‘s core mechanics, which remain largely identical through most of the series. Even the music, supplied by veteran Yuka Tsujiyoko, maintains the same general style. The first major shakeup occurred with the fourth installment, which introduced a rock-paper-scissors style strength/weakness system, added larger maps and divided the storyline into two generations. Most of these changes were absent from later games, although the weapons triangle remains a staple of the series. The second major shake-up occurred with the 3DS game, Awakening, which added a “casual” mode that removed permadeath, focused on pairing up and marrying off characters, and other changes to make it more approachable to a wider audience.

Oddly enough, Fire Emblem‘s introduction to the gaming world outside of Japan was through the party/action game Super Smash Brothers: Melee for the Nintendo GameCube. Marth was the hero of the first and third Fire Emblem games, while Roy starred in the first, Japan-only Gameboy Advance game. Their theme music is a medley of the Fire Emblem main theme and the “Encounter” theme, which was originally from the first game, but reused in later titles. Rumors circulated that Nintendo of America planned to cut the Fire Emblem characters out since no one in the West knew about the franchise, and outcry ensued. Thankfully, they were left in, as they’re both remarkably good characters to play as. It’s also possible that their popularity convinced Nintendo to localize the later two GBA titles, although Roy’s game never made it to America.

There are fifteen individual Fire Emblem episodes altogether, including two remakes for the Nintendo DS and one for the 3DS. Although none of them are numbered, many fans often address the titles with numbers to make things less confusing (and then NCL made things more confusing by including the remakes in the official numbering on the franchise homepage later).