The mobile game market is often considered a cesspool full of allegedly free games plagued with ads and microtransactions, rip-offs of clones of ancient titles and other useless stuff, but every now and then a genuinely interesting game like Dandy Dungeon comes out. It also is another example of the resurgence of the Japanese gaming industry, which has fallen out of favor with the gamers between the 2000s and 2010s, but is slowly making a comeback. Labeled “The World’s First RPG (Romance Programming Game)”, Dandy Dungeon is the brainchild of Yoshiro Kimura, the weird mind behind games like Chulip or Little King’s Story. Smartphones may not seem the ideal home for Kimura’s usual elaborate universes, but he still managed to inject his trademark zaniness into this game.

Yamada is a typical salaryman who works for Empire Games, a video game company, but is frustrated by his job and would like to make his own games instead of following orders. His wish is granted when he gets fired by none other than Hidemaru Ayanokiji, the chairman of Empire Group, the conglomerate that owns Empire Games and seemingly half of Japan. Now jobless, Yamada is free to create his “Dandy Dungeon” game, and this is where the actual game starts.

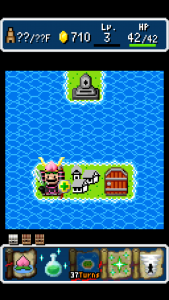

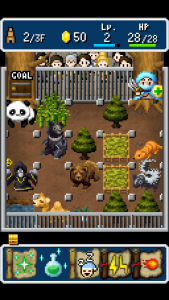

Yamada asks us, the players, to debug it, meaning we have to play the levels he comes up with. As the title implies, it’s a retro-styled turn-based dungeon crawling RPG complete with equipment, treasures, etc., but in practice it’s more like a puzzle game that takes advantage of the touch-screen controls. The dungeons are a grid of 5×5 squares, and the players must create a path with their finger between Yamada’s avatar and the exit door. The avatar will pick up every item he comes across, fight every enemy on the way and destroy stuff that blocks the path. Killing enemies raises his level and stats (he always starts at level 1). The squares that have been crossed also crumble and leave a gaping hole. Covering all the possible squares is not obligatory, but heavily recommended, since a level completed this way will net a “Perfect Bonus” consisting in more money or new useful items. Most of these items can’t be used indefinitely, since every time they get used their cooldown time gets more and more turns to finish, until they finally break, so you have to plan their use especially during boss battles.

Also, every empty (without enemies/items/scenery) square that remains after completion will spawn a deadly will-o’-the-wisp, making Yamada lose energy. The wisps also appear if the players still haven’t connected the avatar with the exit door when the countdown that starts after touching him reaches zero. It’s an interesting system with a good risk/reward balance, and it could be a very nice mobile game on its own, but this is only the beginning.

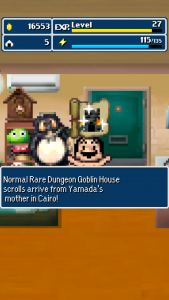

The game is in fact divided into two parts: the actual game described above, and the part where the real Yamada stays in his apartment, furiously coding his game and getting visited by his bizarre neighbors, in true sitcom fashion. Among them there are his friend and former co-worker Yasu, a starving otaku, a wandering monk, a thuggish guy introduced by a Morricone-esque riff, a fat lady who runs an online store (and comes from an ancient tribe of amazons… Get it?), a stereotypical turbaned Indian who’s a genius programmer, and Maria: a pure, innocent schoolgirl who Yamada falls in love with at first sight. (The fact that Yamada loves a girl half his age is also repeatedly pointed out and mocked) Yamada puts Maria in the game as the damsel in distress, and this is what makes the game stand out: interaction with these people inspires him to improve his RPG in some way, and some of them directly help him code new features into it. Or they are put in the game as the bad guys, as happens to Amanokiji and his nasty sons, who all manage to harass Yamada in some way.

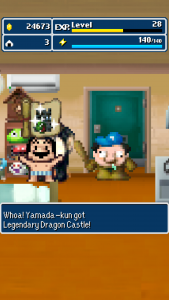

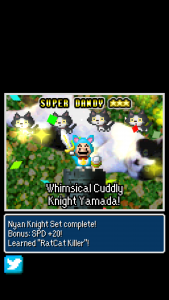

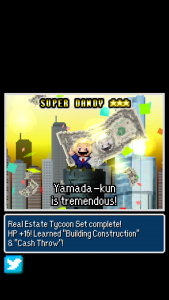

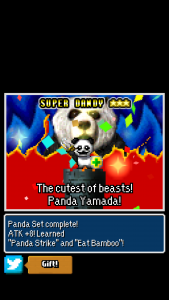

So, what started as an addictive but very basic game becomes more and more complex, with the addition of new settings, consumable items, a shop, randomly generated levels (“Nobody has ever done these”, says Yamada), optional unlockable dungeons, a crafting system and more, becoming more in line with the current gaming generation while still keeping the simple puzzle game core. This works on multiple levels: on a gameplay level it helps the game stay fresh and fun with new surprises at every turn; on a plot level it often offers hilarious justifications on why some dungeons turn the way they are, and also helps the player get more involved with the characters and their struggles (who has never dreamed of turning their boss and his bastard sons into video game enemies and then beating the snot out of them?); on a more general level it all becomes an affectionate mockery of genres, the dungeon crawler and the roguelike, which have become all too common among indie games. And, at the same time, it is a celebration of all the great Japanese games that came before it, Japan’s popular culture, and the resourceful nerds who made games all by themselves because they wanted to. It’s no coincidence that Yamada looks like Mario… and Kimura himself!

The whole “Dandy Dungeon” game is once again a homage to the ever-referenced Dragon Quest and The Tower of Druaga, but there’s nods to The Portopia Serial Murder Case, EarthBound, Ghosts ‘n Goblins, and many more. This is a game where Nobuo Uematsu (sorry, “Nobiyo”) comes to Yamada’s apartment, whacks him with his baton for plagiarizing his music, and then in retaliation Yamada turns him into a game boss who becomes a spaceship or something. It’s all gloriously weird and comical, as expected of Yoshiro Kimura. In fact, there are also several nods to Kimura’s past life experiences: Yamada, much like him, dislikes Japanese corporate culture (represented in-game by the Ayanokoji family), which is portrayed as bad in a very unsubtle, and thus even funnier, way. For example, the “Demon Lord Castle” is actually just an office building full of identical-looking guards. Other features from the older games he worked on are there as well, such as an expansive cast of wacky characters, the use of gibberish syllables for their voices, the blurring between the protagonist’s reality and his games, and of course the importance of love in someone’s life. One additional dungeon, the floating castle of the Thelonious Monkeys, is even a reference to Love-de-lic’s in-house band, Thelonious Monkees, and you’ll have to fight simian versions of the two musicians!

Another addictive element are the clothing items Yamada can find, together they make more than 100 sets, each one giving certain bonuses.

All well and good, but in the end this is still a mobile game, so it has to have some ways to make a profit and keep the players addicted. But they’re far less intrusive than most freemium games. For one, there are absolutely no ads, since Kimura felt they would have broken the immersion. There are items that can be purchased with real money (from the Mamazon store mentioned before!), such as the rice balls that either revive the in-game avatar or refill the actual Yamada’s stamina bar that gets drained every time he enters a dungeon. But one could go through the game without ever buying one, since they’re also given infrequently with the daily login (represented by Yamada cleaning his apartment). The same goes for the keys to the optional dungeon Golden Pyramid, that can either be bought or farmed from the pharaoh enemies that pop up every now and then. There is an one-time purchase, a set of singing ducks that completely remove the wait for the stamina to refill itself, letting one play as much as they want; basically it gives players the opportunity to pay for it without nagging them with pop-ups or other tricks. As many other Japanese games, it also can be linked with a Twitter account, not only to brag after finding or crafting a particularly cool item, but also to download and exchange with other players a big number of stand-alone dungeons, which in turn lead to many other rare items.

The only downsides of Dandy Dungeon (both the app and the in-story game) are that, after completing the main story, it starts to get repetitive, and that some of the legendary weapons need too much grinding to find all the required items to craft them. But these problems are hardly exclusive to it, being typical of both the JRPG genre and mobile games. And even then one can also run the levels in fast-forward mode by keeping the finger pressed on the screen after having traced the path for the Yamada avatar.

With its charming and goofy nature, lovely pixel graphics, catchy “vocal” soundtrack, deceptively simple art and gameplay, Dandy Dungeon puts itself well above most gaming apps and “retro” games that are only superficial imitations of the titles they try to recall.

Dandy Dungeon II: The Phantom Bride

Dandy Dungeon II, the add-on sequel to the game, was made available on Western markets on June 29, 2017 to those who completed the game’s main story. It starts exactly after the end of that one: after having defeated Ayanokiji, Yamada asks his daughter Maria’s hand, but she gets kidnapped right after the wedding (the titular “Phantom Bride” is her) by the goons of Dark Solid Company, a foreign gaming company that bought out Ayanokiji’s Empire Group. Yamada’s neighbors and Ayanokiji’s loyal followers (plus new character “J”, a homage to old man Watari from “Death Note”) then form a committee in order to investigate Maria’s disappearance and also Dark Solid’s fiendish plots.

This time the game-within-a-game angle takes a back seat to the game’s comical version of Tokyo’s metropolitan area. In fact, the investigation shows that Maria has last been seen in some stations of the Yamanote Line, one of the world’s busiest railway lines. Yamada has to fight through several dungeons corresponding to said stops of the Yamanote Line to collect evidence, needed to discover what happened to Maria and what’s going on with the bizarre “Duperhumans” that are popping up in Tokyo. The traditional video game dungeons have been replaced with places inspired by those stations’ landmarks, including stores, parks, zoos, schools, cemeteries, temples and more. Non-Japanese people most likely won’t get most of the cultural and geographic references, but it’s not necessary to know them to enjoy the gameplay and zany humour.

The actual gameplay in fact remains largely the same, with one important difference: these new dungeons are classified as “Missions”. This means that each one of them has a condition that needs to be fulfilled, or else Yamada’ll be booted from the dungeon right then and there (or, in some cases, the access to the dungeon will be outright denied). For example you’ll have to rescue all the cats, defeat enemies in a certain order, always get a “Perfect Bonus” completion, wear specific gear and so on.

This idea however has both a good and bad side. The good: the conditions make the levels more varied and akin to a puzzle game, where brute force is not important, but rather careful path planning and clever use of the items’ and weapons’ abilities. After all, this is the sequel and the player has to show what they learned after defeating the Ayanokojis. Some of these are funny and unexpected, like the school where you get quizzed on several aspects of the game by a robotic teacher. The bad: the difficulty of the missions is too uneven because of said conditions, which in some cases are rather strict or unclear, or because of certain boss battles that are way more difficult than others. Also, some of them are nasty in that, even if you defeated the boss, you still can fail the level because of the conditions, and when that happens it is pretty frustrating. Not to mention the fact that some of them need to be replayed until you get all the ten pieces of evidence required to unlock the entrance to the final dungeon. The randomized placement of items and enemies can also be an additional obstacle, especially in the rescue missions, if you don’t exploit the items’ effects.

In the end, those who loved the main game will probably adore this sequel as well, but those on the fence could probably do without, likely finding it too strict and “too Japanese” for its own good.

Links:

Dandy Dungeon Official site.

Gamezebo Tips and strategies.