In February 2012, Tim Schafer launched a kickstarter campaign for a Double Fine adventure title, marking his return to the genre after fourteen years. With his name on the likes of Grim Fandango and Day of the Tentacle, people went nuts over the thought of one of the greats returning to his genre of choice, and his $400,000 goal was broken apart by a $3.45 million finish. Ironically, Schafer’s goal was to fund a game development documentary, with the production of a new game as a side part of that larger project. Things ballooned. Broken Age was the end result, and this game ended up making crowdfunding a viable option for game developers, both indies and old vets trying to get back into the scene. However, because the campaign had no concrete information on what the game could end up being, people went wild with ideas and expectations for the title, so when it finally released in 2014, it was scorned by many. It did not help that the game was released in two halves, as Double Fine went over budget and instead used profits from selling the first “act” to fund the second (though they were kind enough to make the second act a free update for those who had the first upon its completion). The bad business decisions hurt the company’s reputation with some, and the resulting game wasn’t the new classic people expected.

But that doesn’t mean Broken Age is bad, mind you. Broken Age is something from the aging father Tim Schafer, who wants to make whimsical little games alongside his black comedies. It’s also a bit different from both those categories: It’s Schafer reflecting on his own life and trying to impart something to his audience.

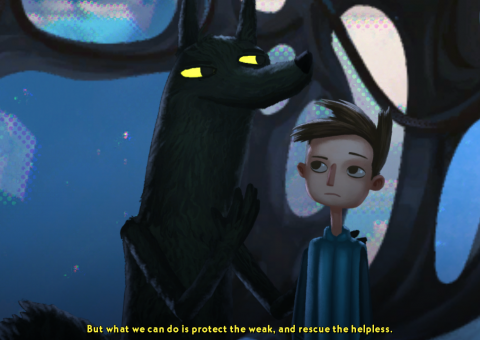

Broken Age has you playing as two characters in very different settings. First is Vella, a girl living in a fantasy world. A monster named Mog Chothra has come to her baker village to devour maidens offered to it in sacrifice, as is tradition with Mogs coming every fourteen years beyond the plague dam. Vella chooses to escape her fate as a sacrifice, then decides to destroy the monster once and for all, like her ancestors would have done in their days as warriors. At the same time, we also play as Shay, a teenage boy in space. He’s bored of his hum-drum life exploring the cosmos while being babied by his overprotective computer “mom,” and soon meets a strange talking wolf that promises to help him gain purpose by having him save helpless creatures in other galaxies. The story has you switching between the two as their stories play in parallel, and occasionally colliding in surprising ways.

Broken Age is a really clever game in many respects. Some of the twists are easy to see coming, but some really come out of left field and lead to a bonkers conclusion. Its clear something has to connect the two very different stories, but the game throws out some red herrings to keep the player off the trail. It also does a lot of great stuff with contrast, as while Vella and Shay’s worlds are both silly and comedic, they have very different flavors. Vella’s world is wacky and bloated with different styles and strange characters (such as a hipster lumberjack), while Shay’s is uniform and suffocating. His entire world is in a spaceship surrounded by yarn people and hexagon robots, designed by his over-obsessive computer mother. There’s a massive difference between the openness of one and the closed nature of the other, one encouraging exploration and the other escape. It’s a nice touch and does a great job at making each story feel like its own, and it also makes it when the two switch settings have more impact because of how they react to the new areas.

Those settings do feel oddly empty, though. Shay’s spaceship is understandable, as it’s effectively a prison, but Vella’s fantasy world starts to get tiring to explore rather quickly. There’s little to do in most areas, despite how pretty they are. The second half of the game barely contains any new areas either, which is disappointing. However, the game has truly stellar art design and explodes with personality, especially in the varied character designs not far removed from the deformed style of Psychonauts, but it fails to really make the areas stick out content wise. This is partly because there’s a greater attempt to streamline here compared to old adventure game design styles, but the style used relies more on simplicity to get across an idea than making a narrative dense setting. Wadjet Eye manages to crank out so many great titles because they use every new screen and area to convey information, world-building, and story, but that isn’t the case for most of these areas. This really shows when Shay is traveling around the fantasy world in the second half, not helped by how one note most of the characters in that setting are.

Everyone is defined by simple characteristics, which has advantages and drawbacks. The biggest problem is that most of the cast have a single joke that gets repeated with the other lead character in the second half. This becomes a problem when backtracking. However, this also lets Schafer and whomever helped in writing craft some pretty great jokes here and there with those simple personalities, especially with the talking tree and train passengers. There’s a bit of that old Schafer black humor in there, but it’s not quite as in your face with the more calming art style on display. The whole game feels like something out of a storybook, making the darker gags funnier by contrast. Still, some characters feel very underused, mainly Jack Black’s H’rmony Lightbeard. With as long as the game goes on, there’s a slightly lacking bit of comedic energy to keep the pace feeling quick.

What makes this worth the time are the themes of the story at work. By the ending, the game has made its message abundantly clear, and it’s simple but powerful. Break from tradition to live life they way you want to, don’t be afraid to take chances, and don’t be afraid to look at the world and people around you and speak your mind about the way things have always been. Vella desires a normal life, while Shay wants adventure and purpose. Ultimately, the two simply want to break away from the way things are, and by doing that, themselves and everyone around them grows. That contrast between them also helps differentiate their ultimate arcs, with Vella learning to become more bold and assertive, while Shay stops acting so self-centered and communicates with those around him. It’s shown well through his time in the fantasy world, as he ends up being generally nicer to characters Vella ignored or antagonized to continue, especially with that tree. One of his puzzles even has a pacifist solution, the complete opposite to Vella’s approach. It helps give the game’s ideas balance, showing there’s an importance in having variety in the world.

Broken Age is also notable for the documentary series, Double Fine Adventure!, made during its development, which you can watch for free on YouTube. (Also, check out the campaign to get this featured on Netflix!) It’s a rarely seen look at what it takes to make a game and how it affects those involved, all hosted by Schafer himself. They were released for backers during development and released in full for everyone else later on, and they’re mandatory watching for anyone interested in game development. If the videos were released publicly during development, it probably would have eased some of the harsher critics out there.

At the end of the day, Broken Age isn’t a riot of a title that people wanted. It’s not something that will scratch a nostalgic itch. But it’s not something to be ignored either. There’s something beautiful about it that can grow on a person, and it makes a lot of smiles while it lasts at about ten hour so hours, depending on how good you are at puzzle solving. It doesn’t feel unfinished, just not as great as it could possibly be. But its ideas resonate, and it truly has a style no other point and click out there could ever have.