If Infogrames lore is to be believed, Alone in the Dark first sparked from an idea of company founder Bruno Bonnell, about a game taking place mostly in dark surroundings, forcing players to navigate by sounds and sparse light sources. Nonetheless the actual game started as an independent, non-funded side project inside Infogrames, conceived by tech wiz Frédéric Raynal. A big horror movie fan who had just earned his 3D programming spurs with the PC version of Infogrames’ Continuum, he decided to combine his passion and his skills into a new kind of video game.

Even before the series was revived from its long sleep with the 2008 reboot, there were few gamers who never heard of Alone in the Dark. Whenever the history of Resident Evil was recounted, the games media rarely failed to point out that Capcom’s zombie shocker was deeply inspired by an old French computer game that first introduced fixed camera angles and the struggle with limited resources against an overwhelming opposition of monsters, often making retreat a better option than all-out fighting. But regardless of these defining attributes, Alone in the Dark has been a surprisingly heterogeneous series, both in its settings and in gameplay focus – series hero Edward Carnby has fought his way through two eras, sometimes sneaking around ancient mansions, sometimes gunning down zombie mobsters and pirates by the dozens, sometimes fighting his way through an apocalypse.

Alone in the Dark is also one of the handful Western franchises that made it big in Japan (the Japanese spelling for the title is アローン・イン・ザ・ダーク). All the games were released over there, which explains how it could have such a big impact on the Resident Evil designers. But not only Japan – in Korea the original Alone in the Dark was one of the very first Western PC games that were fully localized, titled Eodumsok-e Nahollo (어둠속에 나홀로), and in China the series is known as Guiwu Moying (鬼屋魔影, “Spookhouse Spectres”).

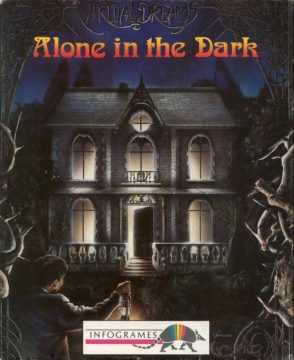

Raynal’s concept for the game was a simple set of ideas: He wanted to create an action adventure game with zombies and monsters, evolving the technology used in Continuum to create articulate 3D characters. The player had to be alone (mainly to save Raynal the headache of dealing with character interaction and dialog) and the game was to be set in an old manor during the early 20th century, a time when electronics and communication weren’t as advanced. His first scenario was only three words long, but perfectly captured the spirit of survival horror: “Get out alive!” With the help of lead animator Didier Chanfray, Raynal created a tech demo of a 3D sphere walking around an attic. The plan initially was to digitize photos from real life locations for the backgrounds, but it proved impossible to reverse-engineer the corresponding wireframes for collisions. So an artist was needed, and through an internal contest Yaël Barroz, who had graduated from a proper art school (and who later married Raynal), was determined as the 2D artist for the backgrounds. Philippe Vachey was recruited for the audio department. Once a first prototype was created, Bonnell gave the green light to produce “In the Dark”, the first of the many working titles for the project. The game was conceived as the first title in a series called “Virtual Dreams,” standalone games that would all use the same engine. The label is even featured on the original French cover, but contrary to the Alone in the Dark franchise, it never took off.

It’s Louisiana, 1924. Famous painter Jeremy Hartwood is found dead in his gigantic mansion Derceto. Most of his recent paintings show grotesque monsters and unspeakable horrors. It appears someone or something slowly drove him insane. Eventually, he hanged himself in his own attic. Two persons have a strong interest for the late Mr. Hartwoord’s mansion: the iconic series hero Edward Carnby, hard-bitten private eye, and Emily Hartwood, gentle soul and the niece of the poor sod. As soon as they enter the mansion, both quickly realize that something is wrong with Derceto and that Hartwood was actually haunted by real nightmares. Will they find out the truth, or die at the hands of the unspeakable horrors?

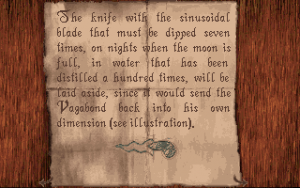

Although it is a bit thread-bare, Alone in the Dark’s story still manages to be coherent and immersive. Most of the narrative is entirely optional and can be discovered by reading ancient books & various correspondences, long before Bioshock or even its predecessor in spirit System Shock. The writing reeks of Cthulhu influence: Carnby is named after the protagonist in Clark Ashton Smith’s short story “The Return of the Sorcerer,” which is considered the first Cthulhu Mythos work by another author than H.P Lovecraft, and many typical Lovecraftian monsters such as Deep Ones and Cthonians are present. Hubert Chardot, the main writer for the game, was a huge fan of the Cthulhu mythos, which should explain the heavy similarities of the pitch. Infogrames was actually in talks with Chaosium to apply the Call of Cthulhu license for the game as well. Raynal welcomed the rich mythology the franchise offered, but was worried management would impose RPG elements like character sheets on the game. In the end Alone in the Dark was judged not faithful enough to the pen&paper RPG to make the cut. (Chardot got to work on “proper” Cthulhu games eventually – he was on the writing team for both Shadow of the Comet and Prisoner of Ice.)

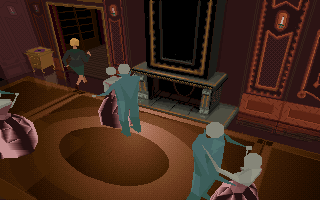

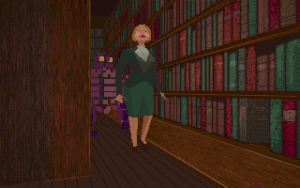

As the grandfather of what we know today as the survival horror genre, Alone in the Dark shares many characteristics with Capcom’s clone Resident Evil. At the beginning, the player gets to pick between two characters, each with their own background story, but the quest remains identical regardless of the choice. Carnby and Emily navigate freely as 3D characters through pre-rendered rooms, introducing the infamous tank-controls to the genre. They’re even weirder than in most other games, since the camera changes are often not quite as well thought-out as one would wish, and running requires a very awkward double-tap motion that only seems to work when it feels like it, while the standard walking speed is excruciatingly slow.

But Alone in the Dark also possesses some quirks that didn’t make the transition to its imitators. The first big difference resides in the action screen, a menu where one can glance through the equipment, check the hero’s health and select one of several actions. The basic ones are Search, Fight and Push; only during the last passage of the game, Jump is activated. The commands also apply to the inventory, for items such as weapons, health-kits, books, etc. possess different functions. Inventory space is limited, and items can be thrown and dropped anywhere – a feature that the Resident Evil series only took ten more years to adapt with Resident Evil 0. Jokes aside, the difference between putting items in certain places and simply “using” them is also relevant to many of the puzzles. Light and darkness didn’t play quite as big a role as in Bonnell’s inspiring idea, but there were still pitch dark rooms that had to be illuminated by a light source, like in Maniac Mansion or many older adventure games.

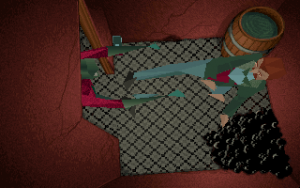

Zombies, rats, ghouls and ghosts are among the various creeps that await you in Derceto. Don’t be fooled by their rather goofy appearance, though. They all can be pretty dangerous if you don’t pay attention. In hand-to-hand combat, different attacks can be executed by holding Space and pressing any of the four directions, resulting in a head butt, quick jab, fierce punch or high kick. Each move has a certain reach, speed and power; the main goal is to stun lock enemies so they can’t stun lock you. As simple as it sounds, combat can get infuriating when the enemy locks you in an infinite combo. In addition to various melee weapons, a pistol, a shotgun and a bow can also be found in the mansion, but ammo is scarce: Six shells, twelve bullets and three arrows (one of which is required to disarm a trap) are all there is for the whole game. Unlike many later survival horror games, Alone in the Dark isn’t simply a horror-themed action game with quirky camera angles; most of the enemies must be scattered through wits, and direct confrontation is often not the best option most of the time. In the first room, for example, the player gets subsequently attacked by a werewolf jumping in through the window and a zombie rising from a trapdoor; both can be kept in check by moving pieces of furniture in the way.

After escaping from the rather linear second floor, Derceto allows players to choose their own demise. There’s no way out before dealing with the evil that lurks under the mansion, but otherwise you’re free to explore. There are items indispensable to proceed to certain rooms, like magic protection, a lantern or keys, but many can be reached in any order. The puzzles are fairly easy, and usually clearly hinted at through in-game references and books. In some cases mistakes can result in dead ends and make the game unwinnable, though. There are also a lot of mean instant-kill traps. That isn’t too much of a problem, though, as the game is fairly short and built around learning through failures for the next attempt rather than just guiding players through the adventure in one linear session.

The new technology allowed for an adaption of cinematic techniques unprecedented in video games, which provided the ideal means to shock the player. Monsters suddenly appeared from off-camera corners of the room, often intentionally placed in angles that would compromise the player’s sense of direction. The uncertainty of what unspeakable horrors may lie around the next corner terrorized players more than any other game before. There’s even an almost POV-shot from an attacking monster, as well as the introduction of a series trademark: Almost all Alone in the Dark episodes (only the 2008 reboot would dispose of this tradition) feature an early view out of a window, implying a frightening onlooker as the hero approaches the danger zone. The character models with their crazy eyes, clamshell hands and pointy breasts may look like a joke nowadays, but no one can deny the craftiness in setting the game in scene.

But camera tricks only accounted for half the horror. Philippe Vachey is one the most famous composers in French video game industry. Using water-phone and various instruments, he delivers an uncanny mood that fits perfectly to the whole haunted house stereotype. The sound effects are of course as creepy as expected; the wooden floor creaks under every step, and unsettling jingles announce that something wrong happened nearby. Some sound effects were also put randomly at certain places to further add to the player’s feeling of uncertainty.

A CD-ROM version soon followed, which introduced a Redbook audio version of the soundtrack and voice over for the character descriptions and all written documents found in the game. The quality of the voice acting is what one would expect from a game in the early 1990s – at least in the English version. For once, the original French voice acting is excellent, as most of the voice actors come from the theatre scene. Because it’s slower than average reading speed, it’s really more of a distraction than anything, though.

The game was a critical and financial success, with Infogrames founder Bruno Bonnell reaping most of the praise. Raynal and his team didn’t intend to put up with that. Chardot stayed with Infogrames for many years, but the rest of the core team went off to found Adeline, where they created Little Big Adventure and Time Commando, which used an engine similar to Alone in the Dark.

Despite its success on the IBM PC, Alone in the Dark wasn’t ported to that many other platforms. The timing certainly played a role here – the game arrived too late for an Amiga or Atari ST version to be worth the trouble, and too early for the mainstream next gen consoles. The game did make it onto Acorn’s obscure 1980s high-end computer Archimedes and to various Japanese 16-bit computers, who suffer a bit in the audio department, but otherwise look and play identical to the IBM version. The only version that features “improved” graphics was for Macintosh computers, which uses double resolution, with a visual filter applied to the 2D backgrounds.

The only console port was made for the 3DO. It had to make some compromises with the character models and used a noticeably lower resolution for the main view, but brings one important improvement: There’s now a separate running button, making the controls much more sufferable. It also has the questionable benefit of the voice acting from the CD-ROM version, alongside the not at all questionable redbook soundtrack.

Comparison Screenshots

Window Lookout Shots

Jack in the Dark – IBM PC (1993)

Jack In The Dark is a neat little promo game that kinda functions as a demo for Alone in the Dark 2. It was packed in golden wrapping with the face of a jack-in-the-box on the unique floppy disk, and also included with CD-ROM versions of the main games.

Rather than containing a portion of the actual sequel, Jack in the Dark introduces a nice little Christmas tale. Grace Saunders, a small child wandering in the streets, ends up locked in a toy store. But she’s not alone Santa Claus has been locked inside there too, by an evil Jack-in-the-box (who bears the likeness of the villain from the second game). Of course, as a child Grace can’t really fight her way out and so she has to solve a few puzzles to put the living toys at rest and restore the spirit of Christmas. It ends with grace being captured for the events of the second full game.

While it takes only about fifteen minutes to complete, this little escapade is still fairly enjoyable, if only for the cheerful and nostalgic atmosphere.